- Home

- Shirley Jackson

Hangsaman Page 15

Hangsaman Read online

Page 15

“Anyway,” Anne said, “you give Lizzie a drink, and she doesn’t care if you spread the cheese with the bottom of your shoe.”

“Look,” Vicki said, turning from Anne to Natalie. “What about Lizzie drinking? Shall we make her take it easy?”

“I really think she’ll behave herself since she’s not in her own house,” Natalie said.

Vicki laughed. “If she’s within reaching distance of a bottle? ‘They’re all so jealous of my catching Arthur,’” she said in a high whining voice. “‘No one understands that I only want everyone to love me.’”

“I don’t think it’s any of our business,” Anne said in her sweet voice. “After all, we can’t presume to judge her behavior.”

“Well, if Arthur doesn’t care, I don’t,” Vicki said. “Listen, there’s the doorbell.”

She ran out of the door and down the stairs. They were entertaining in what might be called Vicki’s room, which made her nominal chief hostess; Vicki’s room and Anne’s were on a corner of the second floor of the house, and were prized by all students as the most desirable location on campus. Vicki and Anne had kept the corner rooms for two years; they had lived here together through two years when these rooms must have been more intimately home to them than the island Elizabeth Langdon despised, or the other homes they knew where the rooms were larger and the service better. The room which was listed as Vicki’s in the college offices had been made into a study, and Anne’s room a bedroom; they entertained, naturally, in the study. This room proudly held less of the college furniture than any other room on the campus; the bookcases were recognizably institutional furniture, but then, as Anne had told Natalie reluctantly, bookcases that size were so difficult to transport, and the wastebasket was an undeniable college wastebasket. There were, besides, a studio couch, and a coffee table, and a modern lamp. The pictures on the wall had been painted by Vicki in her second-year art class, and were beautifully framed; the books in the bookcases showed precisely which classes Vicki and Anne had attended during their college years, and gave an occasional sense of their having sampled all the possible courses given at the college in order to learn the names of the textbooks. The blockprint on the curtains had been especially designed for a whimsical sort of person by someone who could afford to do so, the rug was softer than most college beds. How this room could exist not more than one floor and half a dozen doors from her own bare small room on the third floor was a matter of continual surprise to Natalie, and it seemed to her frequently that Vicki and Anne had moved in here, and stayed here, only as some kind of a concession which they made with their usual courtesy to the college authorities.

Possessed tonight of a part-interest in the room, by right of the crackers and cheese she had supplied, Natalie rose with dignity from the studio couch and came to stand in the doorway with Anne, careful not to come too close. They could hear Vicki greeting the Langdons downstairs. “So glad you came,” Vicki was saying, and “Come on upstairs, Nat and Anne are waiting.”

They could hear the Langdons coming up the stairs before they could see them rounding the turn halfway. “I wish . . .” Anne said, and then was silent. What would she have said if I had been Vicki? Natalie wondered, and felt Anne sigh and saw Elizabeth Langdon coming up the last part of the stairs. She was dressed up, perhaps more than the occasion demanded. She was wearing a dark-blue dress, very tight at the waist and full in the skirt, with a low-cut neck and much heavy jewelry; it was a dress more fitting for a student than for a faculty wife, with its pretty cut more suitable for a date with a college boy than a cocktail with three college girls. Perhaps Elizabeth had felt this when she dressed, because she had added to her costume a most mature hat, with a caught-up veil and a frill of small feathers, not at all the sort of hat which might be worn by anyone who described herself as a “pretty girl” rather than “an attractive woman.” She looked, altogether, very handsome, and would have looked far handsomer if Anne had not been wearing a soft rose wool dress which touched up the highlights in her blonde hair. Natalie had spent some little time over her own clothes and felt more gaunt and ungraceful than ever, standing in a small circle with Elizabeth and Vicki and Anne; but, she thought to console herself, no one is looking at me anyway.

For a minute they hesitated in the doorway, Anne’s excessive good manners not adequate to induce Elizabeth to forgo an entrance and come into the room normally. At last, by judicious edging backward by Natalie and Anne, and tactful urging from behind by Vicki, Elizabeth was subtly introduced into the room and seated in an armchair; she tried to go to the couch to sit in what was most closely approximate to her own spot at home, but was forestalled by Vicki, who insisted upon the armchair. Elizabeth sat, then, uneasily, with the two bookcases meeting behind her back and the open windows across from her. Anne sat on the couch next to Arthur Langdon, who had entered the room last, and quietly, as though he had only come along unwillingly with his wife, and Vicki and Natalie hovered uncomfortably over the small table at the side of the room, the one over the tray of liquor and glasses, the other over her cheese.

“You’ve changed things around,” Arthur said to Anne, thus committing with a grand unconsciousness his first magnificent blunder of the afternoon.

“Only the couch and table,” Anne said sweetly. “How do you think it looks, Mrs. Langdon? We find it maddening to make these college rooms look civilized.”

“If you used the college furniture you wouldn’t have so much trouble,” Elizabeth said, moving in her chair. “It looks nice, though.”

“Like a warehouse, actually,” Anne said. “You know, everything piled up together. If we only had some space.”

“Very pleasant place to work,” Arthur said.

“Writing papers for Langdon’s class,” Anne said. Everyone laughed gaily.

“I may think I’m making something here,” Vicki said, over their laughter, “but actually it’s more mudpies than anything else—heaven only knows what I’ll have when I’m through.”

“May I help you?” said Arthur immediately.

“I’d be ashamed,” Vicki said. She lifted the vase they had decided looked just enough like a cocktail shaker to pass if no one examined it too closely, sniffed at it, shook her head dubiously, and said, “Well, how wrong can you go, with just gin and vermouth?”

Arthur closed his eyes in pain, and Anne said to him, “You’d better make the next round.” Vicki began to pour the cocktails carefully into the two good glasses, and Anne said politely to Elizabeth, “You look so well, Mrs. Langdon; that dress is so becoming.”

“You look well, too, Anne.” She has promised Arthur to be civil, Natalie thought with sudden pity; she is pretending to be Old Nick being gracious.

“You look as though you’d been out in the sun all day,” Anne said to Elizabeth.

Elizabeth smiled deprecatingly. “I’ve been doing housework.”

“I sometime think,” said Anne, who was perhaps imagining that she was Old Nick being gracious, “that housework must be really the most satisfying work of all.” Elizabeth stared at her incredulously, and Anne smiled shyly at her and added to Arthur, “It must be wonderful to see—well, order out of chaos, you know that you’ve done it yourself.”

“I suppose you’ve never scrubbed a floor?” Elizabeth asked. She was still sitting very stiffly in her chair, her hands folded in her lap over her suede pocketbook and her gloves. She turned her head to watch whomever was speaking, and when Vicki brought her a cocktail in the first good glass, she accepted it with an unsmiling bow of thanks, and sat holding it poised in her hand. Arthur got the second good glass, of course, and sipped at it immediately in order to nod to Vicki and say, “Very good indeed,” with a faint air of surprise.

“Is it really?” Vicki said. She nodded her head proudly. “I always knew I could do it if I tried.”

Natalie had achieved several unbroken crackers with cheese on them, and she

passed the plate to Elizabeth. As Elizabeth took a cracker she looked up without expression and said to Natalie, “And how are you, my dear? Studying hard?”

“Not hard enough, I’m afraid,” Natalie said. You ought to meet my mother, she was thinking.

“What accomplished hostesses you all are,” Arthur said, when she passed the plate to him.

“There’s a real art to getting cheese on crackers,” Natalie said.

“It’s a talent every young girl should have, making and serving a good cocktail,” Arthur said.

“I’ll have to take lessons, then,” Anne said.

There was a small silence, and then Elizabeth said, “Arthur dear, do you realize that these girls have gone to a vast amount of trouble and expense just to entertain us?”

“I think it extremely kind of them,” Arthur said gallantly.

“You were very kind to come,” Anne said, and Vicki said, “It’s a pleasure to us, too,” and Natalie said, “Yes, indeed.”

“I am sure we were both delighted to come,” Elizabeth said. She sipped daintily from her glass and said, “Quite a good cocktail, Vicki.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Langdon,” Vicki said.

“What do you hear from your father?” Arthur asked Natalie.

Natalie laughed. “He said if you hadn’t read his piece in the latest Passionate Review, I could use its arguments to confound you.”

Arthur was delighted. He laughed, and drank deeply from his glass, and put the glass down, and laughed again. “Splendid,” he said largely. “As a matter of fact, I haven’t gotten to it yet, so you would have a real advantage over me.”

“I haven’t read it either,” Natalie confessed, and this further delighted Arthur.

“I don’t think Natalie ever reads Daddy’s articles,” Anne said in her soft voice. “Vicki and I got the Passionate Review from the library and frankly I—” she smiled, managing an unexpected dimple “—couldn’t understand a word of it. I could no more manage to confound anyone . . .” She moved her hands helplessly. “Nat is so smart,” she said.

“We’ve been dying to meet him,” Vicki told Arthur, “but Nat is ashamed we’ll disgrace her by looking like fools.”

“Which we would,” Anne said. “Can you imagine me telling Daddy I couldn’t understand a word he wrote?”

Natalie, who could precisely imagine Anne telling her father she could not understand a word he wrote, said with amusement, “I think he’d be flattered.”

Anne said to Elizabeth, “We’re all afraid of Nat anyway; do you know she writes the most wicked descriptions of all of us to her father? I positively dream sometimes of what Nat is telling Daddy about me.”

“Is that so?” Arthur asked with interest. “I never saw any of this.”

“What sort of thing do you write, for instance?” Elizabeth asked with sudden real curiosity. “All about everyone you know?”

“That’s not a fair question to ask anyone, my dear,” Arthur cut in smoothly. “Natalie and I have discussed her writing very conscientiously,” he added, and Natalie, remembering their conscientious discussion of her writing, was tempted to describe it to Elizabeth. “And,” he continued, “believe me, I have the greatest faith in Natalie’s talent.”

Elizabeth turned her eyes from her husband to regard Natalie for a long minute. Then she said, “I suppose that sort of thing is all right to do until you’re married.”

“And after you’re married,” Anne said lightly, “you’re too busy doing housework.”

“May I pour anyone another drink?” Vicki said. There was a silence while they all consulted the contents of their glasses. “Thank you,” said Arthur, and, “I’d like one,” from Anne.

“Mrs. Langdon?” said Vicki. Everyone avoided looking while Elizabeth glanced down at her glass, barely touched. She shook her head, turning slightly to her husband. “No, thank you, my dear,” Elizabeth said.

Everyone had another cocktail except Elizabeth and Natalie, who was beginning to feel that she had seen more drinks than books in her first few months of college. In one of her letters to her father she had told him, “I am beginning to think that the symbol of college, at least for me, has been a kind of drink I never remember seeing much before. Martini. What do you suppose the name means? I know the names of most drinks have no sense to them anyway, but this one sounds like it had been named after someone; do you suppose he could have been a college president?”

Her father had written back: “A martini is a sort of cocktail (which I do not, myself, regard with great enjoyment) served exclusively and drunk exclusively by a clearly defined type of person. As far as my experience makes it possible for me to judge, this person is usually volatile, high-strung, and excitable. All of these are qualities shared by good vermouth, which is one of the ingredients of a martini. Another ingredient is gin, which is feminine and appears more harmless than it is: another characteristic of your martini-drinker. The third ingredient of the martini is bitters, and I need labor my metaphor no further, I hope. I will add that the drink is served ice-cold, that some people prefer to have the ingredients shaken, some prefer them stirred, that it is possible to refine one’s position with regard to the martini by discarding the traditional olive, and passing along further stages of refinement through the black olive, the twist of lemon peel, to the final, most effete, pearl onion. It is thus possible, you will perceive, to express the most exquisite shadings of personality—but I believe I have made myself more than clear. From this you should be able to believe without taxing your forming critical mind that by definition the martini is a natural college cocktail.”

“We have to be at the Clarks’ at six,” Elizabeth was reminding Arthur.

Arthur nodded. “Plenty of time,” he said.

“I’m so sorry,” Anne said to Arthur. “We hoped you’d go into town later and have dinner with us.”

“Our engagement for tonight is of several weeks’ standing,” Elizabeth said grandly, sipping then at her drink with her eyes on Anne. “Naturally we can’t disappoint the Clarks, but I told Arthur you girls would be so unhappy if we didn’t come here first, even for just a few minutes; I really had to persuade him to come.”

“So glad you did,” Vicki said. “Another drink?”

Elizabeth looked again into her glass, and again at Arthur.

“I thought I’d never stop laughing, this morning in class,” Anne said to Arthur at that moment.

Vicki said quickly to Elizabeth, “They’re terribly weak.”

“Weak?” Elizabeth said. “Weak. They are weak.” She made the word sound comic, and she handed over her glass. Vicki filled it quickly and brought it back, and then sat down next to Elizabeth, on the floor with her legs crossed. Natalie, who was sitting on the floor with her legs crossed on the other side of Elizabeth’s chair, moved to sit at precisely the angle Vicki adopted, and Vicki clearly and deliberately nodded at her, as though to say: We’re doing beautifully; good work.

“I love that pin,” Vicki said to Elizabeth lavishly.

“Thank you,” Elizabeth said coldly; it was to be clearly understood that she did not like Vicki and she did not court flattery.

“Will you look at the colors in that pin?” Vicki said to Natalie. “Have you ever seen anything so lovely?”

“Beautiful,” said Natalie. “Enamel, isn’t it?”

“I believe it is,” Elizabeth said to Natalie. It was to be clearly understood that while she did very likely regard Natalie with some favor, she was not prepared to commit herself until she found out exactly how far Natalie was in turn committed to Vicki.

“I wish I could make you understand how much we all admire you,” Vicki said to Elizabeth. “All the things you do—taking care of your husband and your house, and keeping up with classes, and still somehow managing to look so lovely all the time, and everything.”

Natali

e, thinking, She surely cannot accept this seriously, heard with surprise Elizabeth saying with modesty, “Well, of course, I don’t really . . .” and Vicki interrupting smoothly, saying, “Another drink?”

* * *

At six-thirty, then, Elizabeth sat up suddenly in her chair and said, “Arthur, what time is it? We have to go to the Clarks’.”

“Plenty of time,” Arthur said.

“We have to go the Clarks’ for dinner,” Elizabeth explained to Vicki and Natalie. “They must be expecting us because they’re expecting us for dinner.”

“It’s very early,” Vicki said.

“Plenty of time,” Natalie said.

“Have another drink,” Anne said, and giggled.

Natalie was reciting to herself, softly, “Around the campus and double quick, Have a drink with Annie and Vick; Vick’s the butcher, Anne’s the thief, And Langdon the boy who buys the beef.” She thought she had better not copy this out to send to her father; she was not, at this point precisely sure of the metre. It seemed to her that she had spent too long sitting in one position, and she got up and stretched lazily.

“Where you going?” Elizabeth demanded immediately. “We’ve got to go to the Clarks’. Arthur?”

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

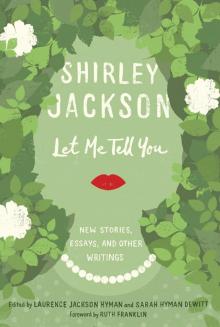

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You