- Home

- Shirley Jackson

Hangsaman Page 14

Hangsaman Read online

Page 14

“It certainly is not,” said Elizabeth, and shuddered. “My God, I was scared,” she said.

“Me, too.”

“Well,” Elizabeth said, as though done with the subject. “How about we finish off the cocktails?” she asked.

Natalie made a face. “I don’t know if I can stand it,” she said, and gestured at the room at large. “Seems like it’s into everything.”

“You won’t notice it after you’ve had a drink,” Elizabeth said. The shaker sat on the table where she had put it down, and she picked it up and looked into it again. “There’s really quite a lot left,” she said, and carried it with her out into the kitchen to get glasses. While she was gone Natalie opened the window and stood looking out onto the college campus. Somehow, inside this room, in the house, she was removed from those girls in their bright sweaters who walked easily across the grass, under the colored trees, ignoring the paths and putting their clean brown-and-white shoes down as though their tuition had bought them a permanent share in this very land. They understood the functioning of the college, these girls outside, talking to one another as they walked, and knowing the places to which they were bound; they were intimate and sympathetic with this college, and never saw it as the spot where Arthur Langdon taught, or where one was held apart from home and kindness by the dubious good intentions of strangers. Inside here, Natalie thought, turning abruptly to look into the room and at the furniture and books and even the burned couch, inside this room is the only place except my own home where everybody knows my name.

“At least two drinks apiece,” Elizabeth said gaily, “and probably more.”

“Hadn’t we better save some?” Natalie said prudently.

Elizabeth’s face turned sullen. “At least this time,” she said, “he won’t be able to say I drank them. This time he can’t blame me.” She looked at the couch. “He can’t even be angry at that, very well.”

“I don’t think it’s badly burned,” Natalie said.

Elizabeth shrugged. “Oh, well,” she said, and sat down on the couch; because her favorite corner was burned she was forced to go to the other end, and she sat there uncomfortably, resting on her wrong elbow. “I was reading,” she said, looking irritably at the burned spot. “That’s what happened, I was reading.”

“Next time put out your cigarette before you fall asleep.”

“That’s what I get for reading,” Elizabeth said. She pointed with her toe to the book on the table. “Psychology,” she said. “I can’t understand it.”

“Then why do you do it?” Natalie asked, wondering at the vast freedom of one who could learn if she chose and could, if she chose, flatly refuse to understand.

“We all do it,” Elizabeth said. “All of us, the faculty wives. Got to do something, you know. And besides, it feels good to sit next to those kids in class and look at them frowning and trying to make something out of it, and you sit there thinking how much more you know than they do, and they have to call you Mrs. Langdon.”

“At least you don’t have any trouble passing.”

Elizabeth made a face. “I never finish up the courses,” she said. “Those poor kids, they have to come rain or shine, and answer when they’re asked questions—me, I can just say, ‘Go to hell professor,’ and walk out if I’m bored.”

“How about your husband’s class?” Natalie asked.

“I took that class,” Elizabeth said, and laughed. “I got through the whole thing—and I passed, too—before I ever married Arthur. He used to give me back my papers with notes written on them. I’d laugh out loud, sometimes, in class when he gave me my papers back with those notes on them. And he’d read things like speeches from Antony and Cleopatra, and some of the kids would be blushing and some of them would be just looking at him like lovesick chickens, and I’d think of how anytime I wanted I could get him to read the same things to me all alone and I’d look around that class and think how pathetic those kids were and I’d want to laugh in their faces.”

A great envious excitement filled Natalie; she promised herself quickly that she would somehow, later, examine how it would feel to sit in class with such special secret knowledge, with such delicious sense of possession.

Elizabeth sighed. “I liked that class,” she said. She was smiling reminiscently still as she rose to fill Natalie’s glass. “And sometimes,” she said, “I’d meet people like Mr. and Mrs. Watson—he was biology teacher then—and I’d say, ‘How do you do, Mrs. Watson, Mr. Watson,’ so politely, and all the time I’d be thinking of how when Arthur and I were married I could call them Carl and Laura. And about sitting with the faculty at trustee dinners or college movies. And running into Arthur’s office whenever I pleased, and not caring who saw me. And staying out all night if I felt like it, and laughing in anyone’s face the next morning. And faculty parties,” she said, “and pouring at teas. And getting the best of everything.” She sighed again, her head on her arm and her long hair falling against her face. “I thought it was all going to be so wonderful,” she said.

Suddenly, again, Natalie felt the small chill of dismay when Arthur Langdon’s footsteps sounded outside the door and, with the opening of the door, the same familiar shock of finding him slightly smaller than she had remembered him.

“Hello?” he said, blinking after the bright sunlight outside, and then, his voice hard, “Smells like a brewery in here.”

Elizabeth stood up quickly and hurried across the room to him. “Arthur,” she said, and her face showed alarm but her voice was rich, “Arthur, listen, I tried to kill myself again this afternoon—”

* * *

It was on a Thursday evening early in November that the peculiar events in the dormitory where Natalie slept began to attract attention. On that Thursday evening (there was a full moon, which several people insisted hysterically had certainly something to do with it) the girl who lived alone in the room almost directly under Natalie’s arose from her bed asleep and unlocked her door and moved slowly and with seeming purpose down the hall. Where she could, she opened doors and went in to awaken all sleepers. At each bed, the story went, she bent over gently and smoothed the pillow, before giving the girl asleep a quick slap to awaken her. “No sleep tonight,” she told each of them pleasantly, and left the room. By the time she had reached the end of the hall a group of girls had gathered, half-asleep and frightened and talking among themselves in whispers. One girl who found herself more competent than the rest separated herself at last from the group, and, approaching the sleepwalker, threw a blanket around her; then half a dozen girls of great courage half-carried the sleepwalker—now walking awake—and shut her into the closet of her own room with the door locked, where she stayed all night, crying and promising to behave if they let her out.

The next night—that would be Friday, with the sleepwalker safely in the infirmary—word of thievery again spread through the house. Natalie, who had not been awakened the night before, was tonight on the outskirts of the group that gathered swiftly in the hall—almost as though everyone had been waiting for some new excitement—when one of the girls announced that she had caught another girl coming out of her room with a blouse in her hand. Miss Nicholas was quickly brought from her bed—she too had missed the excitement the night before, although she had been notified in time to let the girl out of the closet before breakfast—and, with judicious attention to all those who had something to tell her about things stolen, and with sober announcements about being sure before any charge was brought, searched thoroughly the room of the girl accused, assisted by the accuser and several friends. Although none of them were able to uncover any of the stolen articles, it was said and echoed that the girl could have sold the clothes and spent the money. One or two most subtle minds, who volunteered to help the girl tidy up her room after the searching party had finished, reported later in the smoking room that she had said nothing which might be construed as incriminating.

> On Sunday afternoon, while most of the girls and Miss Nicholas were at Sunday dinner, one of the girls on the top floor, who had stayed away from dinner because she had to lose two pounds by the next weekend in order to fit into the dress she was wearing to a houseparty dance, walked out of her room and saw a man running down the stairs. It was decided that he was a Peeping Tom, and several of the girls recalled having seen someone in what must have been that same brown coat hanging around outside the dormitory, as though he were a janitor, or something. One of the girls, who had been severely surprised when she was eleven years old by a man who exposed himself before her as she passed him on the street, explained that this was a kind of neurosis some men had. Many people recalled having heard that such things happened frequently around women’s colleges, and one girl left school because she wrote her mother some of the things she heard around the smoking room.

A senior girl, questioned in the smoking room, said that such things always came in waves. It was a college season, she explained. She told some of the things that had happened during comparable seasons when she was younger, and added that she believed it had something to do with the fact that the Thanksgiving and Christmas vacations were due soon. “Some people have trouble adjusting between college and home,” she explained.

The girl who had been accused of stealing left college, and almost immediately afterward a girl who lived on the second floor reported that her allowance check was missing from her room. It turned out during the next day or so that several people were losing things; one girl went to look for an angora sweater she had put away in her bottom drawer and it was gone; shortly after that, two cartons of cigarettes disappeared from another room, and everyone in the house who smoked that particular brand changed abruptly.

A very brief enthusiasm sprang up for bringing tiny bottles of rum into the dining room and adding the rum to the dinner coffee. This was replaced by an inexplicable and childish two-day enthusiasm for pig-latin. Also in the dining room one evening, an entire tableful of girls rose and walked out in the middle of the meal because they were refused more bread. A girl on the third floor who was seen crying was reported faithfully as suffering from a venereal disease, and a petition was sent to Miss Nicholas to require the girl to use the basement lavatory. Miss Nicholas was reported to be secretly married, and the Peeping Tom identified as her husband, looking for her on the top floor. Two girls in another house tried to kill themselves with double doses of the infirmary sleeping medicine. An unnamed girl, also in another house, was said to have died of an abortion, and several people knew the name of the baby’s father, who was reliably identified as a local man who worked as a lifeguard summers and in the gas station winters. It was generally believed that it was completely possible to become pregnant by using the same bathtub as one’s brother, although not necessarily at the same time.

November 12—Nov. 13

Natalie, my dear,

It is late at night, and I have just come home from a rather ribald gathering, and nothing, it seems to me at the moment, would delight me more than a note of paternal warning to my only daughter. May I—and through how many faulty media—may I, then, issue one note of paternal warning? And over again I reflect on the faulty media—mine own words, the United States mails, the extreme long chance that this letter will reach you at all, that your benevolent housemother (Old Nick, did you say?) should not read this herself and destroy it, that your house should not burn down and this letter with it, that the stamp should not fall off nor the address be erased by some postal cataclysm—suppose, indeed, daughter, it should be one of those letters we read about in the daily newspapers, lost for twenty years, but faithfully found and delivered at the end of that time—how will you feel, twenty years from now, reading a lost letter from your father, with advice well meant and long useless—faulty media? I begin to perceive that it is impossible for this letter to reach you at all.

Let me, then, warn you direfully against false friends. And against those for whose friendship toward you you can find no material motive. And against all fawners, all liars, all nodders. Believe me, girl, without a motive no friendship can be, and without a motive no friendship can last, and whether it be father to daughter or lover to wife, no friendship can come to birth without it have a motive and an end in view.* And further, daughter, I charge you: do not trust entirely to your own knowledge for these things. One person inaccurate upon his own behavior may nevertheless be accurate upon yours. Consult, therefore, the blind and honest; they can do you no harm, and one, at least, wishes you none.

Later

Natalie, I wrote this much last night and would not for the world deprive you of my paternal effusions, particularly since I can see that in spite of my heavy manner, very much, I believe, in the style of an Old-Testament God, I was trying to say something very real, which I must have supposed last night you were old enough to hear. What worries me is, I think, the fact that in your letters you show yourself as not entirely happy. I have been sure for a long time that things were difficult for you, but please remember, my dear, that they would have been difficult anywhere. I chose this college for you because I knew that it was a fairly exclusive, expensive place and, while I pretend to no less snobbishness than any man, it seemed to me additionally valuable in that you will, snobbishness or not, find intelligence and culture accompanying persons of a certain social class. There is no doubt but what the class of girls you have as friends is not a representative one, but my plans for you never did include a broad education; an extremely narrow one, rather—one half, from the college, in people and surroundings; the other half, from me, in information. My ambitions for you are slowly being realized, and, even though you are unhappy, console yourself with the thought that it was part of my plan for you to be unhappy for a while. The fact that you associate intimately with girls who do not care for the things you do should strengthen your own artistic integrity and fortify you against the world; remember, Natalie, your enemies will always come from the same place your friends do. So try to bear with these girls, try not to let their occasional silliness upset you, try not to let them cultivate you for mental values rather than social values—briefly, try to do what I advised last night: scrutinize carefully anyone aspiring to be your friend, examine her conduct for motives, and deny your friendship if your estimate of her motives shows them ignoble. I should, if I were you, be extremely cautious with Arthur Langdon; I have been re-reading his poems. He is a spiritual man, and one to whom things of the spirit are meaningful. Past a certain point this sort of person is not trustworthy; he will expect more of your compliance than you should be ready to give; your humor will offend his mysticism. Do not under any circumstances allow Arthur Langdon to convert you to any philosophical viewpoint until you have first consulted me.

As the person who knows you most dearly, and who loves you always the best, I am equally the one most capable of telling you these things. It has been my plan, Natalie, all of it, and when you approach despair remember that even your despair is part of my plan. Remember, too, that without you I could not exist: there can be no father without a daughter. You have thus a double responsibility, for my existence and your own. If you abandon me, you lose yourself.

Your devoted,

Dad

Being assistant hostess to Vicki and Anne at cocktails was not in any way similar to standing up with Mrs. Arnold Waite to receive guests. For one thing, Mrs. Arnold Waite had been supplied, beyond all else, with the material for bribing people to like her house. On the other hand, since the college had once been progressive, and retained privileges where it had lost principles, students were allowed to own and serve liquor and a minimal amount of food (food, after all, was served in the dining room, but there was no bar on campus) without the conviction, which Mrs. Arnold Waite had to perfection, that it was in any way possible to live differently. Ice might be readily procured at the college store, and carried dripping from a newspaper the length of th

e campus lawn. Toothbrush glasses might be freely confiscated from the common bathrooms, rinsed inadequately, and dried on other people’s bath towels. There were, of course, girls who brought their own sets of glasses to college, and kept them on the bookcases in their rooms, but these were mostly upperclassmen, or girls who realized that their lives were unendurable without the tradition of dressing for dinner.

At the entertainment proffered by Vicki, Anne, and Natalie, the glasses used to serve cocktails to Arthur and Elizabeth Langdon had been borrowed up and down the hall, so that on the front of the tray, with Vicki’s good vermouth and Anne’s gin, bought that morning in town, were two unchipped and matched cocktail glasses, property of someone on the first floor who lent them with the information that if it hadn’t been for Arthur Langdon she would have declined and that, furthermore, Arthur Langdon or not, she would have the hide off anyone who broke them; they had fine gold edges and looked really quite professional. Farther back on the tray, and hidden carelessly behind the gin bottle, were a chipped wineglass, a fruit juice glass stolen from the college dining room, and a plastic bathroom glass; these were for Vicki and Anne and Natalie. On the bookcase next to the tray were a plate, also stolen from the dining room, a jar of cheese spread, and a box of crackers. The cheese was to be spread on the crackers with the wrong end of a nail file.

“You see, the trouble with us,” Vicki said sardonically, surveying their preparations, “is that we try as hard as we can to live up to the standards of the Langdons. We try to make it look as though—”

“If you’d like to take them into town to a restaurant,” Anne said, “you go right ahead. It’s your twenty bucks.”

Natalie, who had supplied the crackers and cheese and felt a maternal obligation toward them, was trying to spread the cheese on the crackers with the nail file; the crackers shattered into crumbs in her hands. “We should have gotten pretzels,” Natalie said. She was still very polite and tentative with Vicki and Anne, sternly repressing in herself the constant question as to why they bothered with her at all. She could have understood their kindness in including her often on occasions such as this, inviting her to the movies, accompanying her to meals, if they had been—say—bored with one another, or needing someone to run errands for them, or amused by her, or respectful of her learning, but none of these estimates seemed reasonable—they were almost too careful of her, so complete in themselves that they needed no one and yet including her with courtesy and insistence, smiling only at her jokes, waiting for her to finish speaking before they began, indifferent to her quotations and yet seeking her company. If they liked her, then, it was for no reason. She had not found yet in them anything to excuse.

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

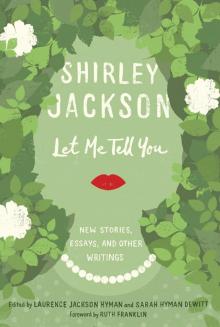

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You