- Home

- Shirley Jackson

Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me Read online

penguin classics

COME ALONG WITH ME

SHIRLEY JACKSON was born in San Francisco in 1916. She first received wide critical acclaim for her short story “The Lottery,” which was published in The New Yorker in 1948. Her novels—which include The Sundial, The Bird’s Nest, Hangsaman, The Road Through the Wall, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and The Haunting of Hill House—are characterized by her use of realistic settings for tales that often involve elements of horror and the occult. Raising Demons and Life Among the Savages are her two works of nonfiction. She died in 1965.

STANLEY EDGAR HYMAN was born in Brooklyn in 1919 and married Shirley Jackson in 1940, the year they both graduated from Syracuse University. Hyman was a literary critic, a staff writer for The New Yorker, and professor of literature at Bennington College, as well as a noted critic of jazz music. He died in 1970.

LAURA MILLER is a journalist and critic living in New York. She is a cofounder of Salon.com, where she is a senior writer. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Los Angeles Times, Time magazine, and many other publications. She is the author of The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia and The Salon

.com Reader’s Guide to Contemporary Authors (Penguin, 2000). She lives in New York.

SHIRLEY JACKSON

Come Along with Me

classic short stories

and an unfinished novel

Edited by

STANLEY EDGAR HYMAN

Foreword by

LAURA MILLER

penguin books

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne,

Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa), Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue,

Parktown North 2193, South Africa Penguin China, B7 Jiaming Center,

27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by The Viking Press, Inc., 1968

Published in Penguin Books 1995

This edition with a new foreword published 2013

Copyright © Shirley Jackson, 1948, 1952, 1960

Copyright © Stanley Edgar Hyman, 1944, 1950, 1962, 1965, 1968

Foreword copyright © Laura Miller, 2012

All rights reserved

“The Lottery” reprinted with permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc., from The Lottery by Shirley Jackson; Copyright 1948, 1949 by Shirley Jackson; first published in The New Yorker.

“The Summer People” first published in Charm; “A Cauliflower in Her Hair” in Mademoiselle; “Pajama Party” in Vogue. Other selections have appeared in Harper’s, The Ladies’ Home Journal, New Mexico Quarterly, New World Writing, and The Saturday Evening Post.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

Some of these selections are works of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

ISBN 978-1-101-61605-5

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not,

by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without

a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means

without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only

authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of

copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For Carol Brandt

Contents

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword by LAURA MILLER

Preface by STANLEY EDGAR HYMAN

COME ALONG WITH ME

FOURTEEN STORIES

Janice

Tootie in Peonage

A Cauliflower in Her Hair

I Know Who I Love

The Beautiful Stranger

The Summer People

Island

A Visit

The Rock

A Day in the Jungle

Pajama Party

Louisa, Please Come Home

The Little House

The Bus

THREE LECTURES, WITH TWO STORIES

Experience and Fiction

The Night We All Had Grippe

Biography of a Story

The Lottery

Notes for a Young Writer

Foreword

Few women with children and husband and household—however happy they may be with all three—have not fantasized at least once or twice about the sort of radical freedom achieved by Angela Motorman at the beginning of Come Along with Me, the novel Shirley Jackson was writing when she died in 1965. Angela has buried her (unmourned) husband, Hughie, sold her house, auctioned off her belongings, and “erased my old name and took my initials off of everything” before leaving town with no particular destination in mind. She arrives in a city, invents a new name for herself, takes a room in a boardinghouse, and begins to give séances. At the age (and dress size) of forty-four, with no connections except to the dead, she is making herself up as she goes along.

Come Along with Me was a late and very welcome literary child for Jackson. She lived with her husband, the critic and academic Stanley Edgar Hyman, and their four children in a big, rambling, book-crammed house in North Bennington, Vermont, and was the commercially and critically successful author of, among other novels, The Haunting of Hill House (made into an excellent film in 1963). Her short story “The Lottery” caused a sensation when The New Yorker published it in 1948, provoking more letters than the magazine had received about any other piece. She had transformed her children’s high jinks into a series of popular, lucrative, and utterly charming humorous essays that appeared in women’s magazines and were collected in two books titled Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. (“Pajama Party” and “The Night We All Had Grippe” in this volume are examples of these pieces; the child characters are based on and named after Jackson’s own kids.) Jackson and Hyman had a lot of fascinating literary friends, including Ralph Ellison, Bernard Malamud, and Dylan Thomas. Their lives, though sometimes disorderly, were also interesting and often fun—anything but the stifling routine associat

ed with housewifery in the 1950s. But to judge from the “fine high gleefulness” with which Angela launches into the unknown, even Shirley Jackson knew what it was like to dream of chucking it all.

Come Along with Me marked a significant point of evolution in Jackson’s work. Previously, her main characters tended to be mousy, neurotic young women who hardly anyone noticed: wallflowers, caretaking daughters, fifth wheels. Angela Motorman, however, is more like her creator, a woman of substance, giving as good as she gets. Yet, as the writings collected here illustrate, even this brave new project hewed close to Jackson’s long-standing concerns and motifs. The twentieth century’s great artist of domesticity and its terrors, her persistent theme was the unspoken and unanticipated prices we pay to belong, whether to a family or to a community.

The fourteen short stories in this volume were selected from Jackson’s previously uncollected fiction after her death by Hyman, who felt they were “those best showing the range and variety of her work over three decades.” The first, “Janice,” may have been a sentimental choice; it was printed in a campus magazine at Syracuse University during Jackson’s sophomore year, and Hyman, when he read it, announced that he would marry its author. (At that point they had yet to meet.) The story is very short, almost sketchy, like a collection of notes, but it has many of the stylistic traits that would later become Jackson’s signatures: the breathtaking confidence that she can pull off a tragic or mad character in a few strokes; the airy, vernacular dialogue that darts at ominous subtexts, then darts away; the precocious awareness that a suggestion is always more disturbing than a shock.

In part due to “The Lottery,” Jackson was and is sometimes referred to as a horror writer. The Shirley Jackson Awards, founded in 2007, honor “outstanding achievement in the literature of psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic” published the preceding year. Stephen King lists Jackson as a major influence on his own work, although their approaches to the supernatural are very different; where King writes epics, Jackson carved exquisite cameos. Jackson, for her part, clearly believed that fear should sneak up on a reader from behind and manifest itself as quietly as a discreet tap on the shoulder. The hauntings in her fiction aren’t often recognizable as such until the end, and only after you think about it a bit. In this, she’s the link between Henry James, who pioneered the same type of highly psychologized ghost story, and contemporary writers as diverse and unclassifiable as Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, and Neil Gaiman. It is her ability to link the homely and the uncanny, the cozy and merciless, that has made her literary vision unforgettable.

Then there are the houses: Jackson’s women are always arriving at a big house, or trying to get out of one. Angela Motorman may have jettisoned the place she lived with Hughie, but in no time she’s ensconced a new establishment, the boardinghouse presided over by the simultaneously hospitable and mercenary Mrs. Faun. Like Louisa in “Louisa, Please Come Home,” Angela seems more comfortable with the transactional relationship between landlady and tenant than she is with family ties—those, in Jackson’s fiction, always seem to be secured with razor wire.

The impression that menace lurks in life’s most familiar precincts, that intimate relations are filled with mortal peril, is the defining mood in the stories collected here. The helpful townfolk of “The Summer People,” the nice little old ladies from next door in “The Little House,” the upright minister father in “I Know Who I Love”—all are out to get the protagonists. Escape is just another a dangerous illusion, not least because without our old tormentors, identity itself can come unmoored. The housewife in “The Beautiful Stranger” rejoices in the belief that the man who comes home to her one day is not, thank God, the husband “who enjoyed seeing me cry.” But if he’s not John, then can she be Margaret? Is she really entitled to another, better life? Among the best of the sinister wonders in this collection is “The Visit,” a variation on a romance or fairy tale, in which the big beautiful country house, a catalog of marvel-filled rooms presided over by a handsome prince, is actually a trap. There’s a crazy old lady in the tower, and she seems to be you.

Then there’s “The Lottery,” a story that has been freaking out readers for decades, with its depiction of a folksy New England town (that quintessential touchstone of American values) routinely turning on one of its own. Jackson’s amused and amusing account of the initial response to “The Lottery,” “Biography of a Story,” shows that the letters forwarded to her by The New Yorker only confirmed her sardonic view of human nature and social relationships. You might assume that the readers of The New Yorker would be cultivated, or at least genteel, she implies, but think again: “What they wanted to know was where these lotteries were held, and whether they could go there and watch.” In an era before Internet comments threads, Jackson’s correspondents gave her a creepily prescient intimation of just how much of the reading public is “gullible, rude, frequently illiterate, and horribly afraid of being laughed at.”

Angela Motorman hasn’t freed herself from people like this, but then who could? They are everywhere. She has, however, finally gotten the upper hand. She doesn’t care if her neighbors pick over her belongings at auction, give her attitude on a streetcar, charge her for the tea and cookies she assumed were offered in friendship. She has her “fine high gleefulness” and (as she mentions more than once) plenty of money. She knows where she stands. Her voice—jaunty, colloquial, and rich in black humor—is Jackson’s. Unlike Flannery O’Connor’s (to invoke a writer of similar temperament whom Jackson admired greatly), it is a voice less celebrated today than it ought to be. But its influence has never died out, and a slow-burning Jackson revival—heralded by the recent inclusion of her work in the Library of America series—continues to grow. Where Jackson would have taken that voice next in Come Along with Me remains unknowable. Angela Motorman might have pulled a message from her out of the ether, but she too, alas, is gone before her time.

LAURA MILLER

Preface

Come Along with Me is the unfinished novel at which Shirley Jackson, my late wife, was at work at the time of her death in 1965. She rewrote the first three sections; the remaining three sections are in first draft.

The fourteen short stories were chosen from about seventy-five not previously collected, as the best, or those best showing the range and variety of her work over three decades. Most of them have appeared in magazines, in slightly altered versions and in a few cases with different titles suggested by the magazine—thus “A Visit” returns to its original title and dedication. I titled “The Rock,” which was found in an early draft, untitled; I cannot imagine why it was discarded, since it seems to me a most impressive story. “Janice” must be one of the shortest short stories on record. Shirley Jackson wrote it as a sophomore at Syracuse University, and it was printed in Threshold, the magazine published by her class in creative writing. My admiration for it led to our meeting. I suppose that I reprint it to some degree out of sentiment, although in its economy and power it is surely prophetic of her later mastery.

The three lectures are the lectures that Shirley Jackson delivered at colleges and writers’ conferences in her last years. “The Night We All Had Grippe” is printed after the lecture she used to conclude with a reading of it, although it appears as a section of Life Among the Savages, since it gets somewhat lost in that book, and I find it the funniest piece since James Thurber’s My Life and Hard Times. “The Lottery” is printed after the lecture that customarily concluded with it, because of the possibility, however remote, that there are readers unfamiliar with it.

The dedication to Carol Brandt, her good friend and agent, was Shirley Jackson’s wish.

I most gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to my children, Barry and Sarah Hyman, and my present wife, Phoebe Pettingell, for help in assembling, selecting, and editing the contents of this book.

STANLEY EDGAR HYMAN

[1968]

COME ALONG WITH ME

1

I always believe in eating when I can. I had plenty of money and no name when I got off the train and even though I had had lunch in the dining car I liked the idea of stopping off for coffee and a doughnut while I decided exactly which way I intended to go, or which way I was intended to go. I do not believe in turning one way or another without consideration, but then neither do I believe that anything is positively necessary at any given time. I got off the train with plenty of money; I needed a name and a place to go; enjoyment and excitement and a fine high gleefulness I knew I could provide on my own.

A woman said to me in the train station, “My sister might want to rent a room to a nice lady; she’s got this little crippled kid.”

I could use a little crippled kid, I thought, and so I said, “Where does your sister live, dear?”

A fine high gleefulness; I think you understand me; I have everything I want.

I sold the house at a profit. Once I got Hughie buried—my God, he was a lousy painter—I only had to make a thousand and three trips back and forth from the barn—which was a studio, which was a mess—to the house. At my age and size—both forty-four, in case it’s absolutely vital to know—I was carrying those paintings and half-finished canvasses (“This is the one the artist was working on the morning of the day he died,” and it was just as lousy as all the rest; not even imminent glowing death could help that Hughie) and books and boxes of letters and more than anything else cartons and cartons of things Hughie saved, his old dance programs and marriage licenses and fans and the like. It was none of it anything I ever wanted to see again, I promise you, but I didn’t dare throw any of it away for fear Hughie might turn up someday asking, the way they sometimes do, and knowing Hughie it would be the carbon copy of something back in 1946 he wanted. Everything he might ever possibly come around asking for went into the barn; one thousand and three trips back and forth.

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

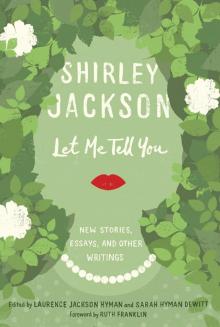

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You