- Home

- Shirley Jackson

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories Read online

Praise for

JUST AN ORDINARY DAY

“Just an Ordinary Day is a long-overdue collection of Jackson’s short fiction…. Jackson at her best: plumbing the extraordinary from the depths of mid-20th-century common. It is a gift to a new generation.”

—San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

“[Jackson] will make you laugh, contemplate your own mortality, and scare you into a wakeful night. And she appears to have done it all equally deftly.”

—The Miami Herald

“An unsettling tale-spinner in complete command of her craft.”

—San Diego Union-Tribune

“For Jackson devotees, as well as first-time readers, this is a feast…. A virtuoso collection.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A welcome new collection.”

—Newsweek

“Psychologically complex and deliciously horrifying.”

—Sun-Sentinel, Fort Lauderdale

Other books by Shirley Jackson

THE ROAD THROUGH THE WALL

THE LOTTERY: AND OTHER STORIES

HANGSAMAN

LIFE AMONG THE SAVAGES

THE BIRD’S NEST

RAISING DEMONS

THE SUNDIAL

THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE

WE HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN THE CASTLE

THE MAGIC OF SHIRLEY JACKSON

COME ALONG WITH ME

Contents

INTRODUCTION

PREFACE: ALL I CAN REMEMBER

PART ONE: UNPUBLISHED STORIES

THE SMOKING ROOM

I DON’T KISS STRANGERS

SUMMER AFTERNOON

INDIANS LIVE IN TENTS

THE VERY HOT SUN IN BERMUDA

NIGHTMARE

DINNER FOR A GENTLEMAN

PARTY OF BOYS

JACK THE RIPPER

THE HONEYMOON OF MRS. SMITH (VERSIONS I AND II)

THE SISTER

ARCH-CRIMINAL

MRS. ANDERSON

COME TO THE FAIR

PORTRAIT

GNARLY THE KING OF THE JUNGLE

THE GOOD WIFE

DEVIL OF A TALE

THE MOUSE

MY GRANDMOTHER AND THE WORLD OF CATS

MAYBE IT WAS THE CAR

LOVERS MEETING

MY RECOLLECTIONS OF S. B. FAIRCHILD

DECK THE HALLS

LORD OF THE CASTLE

WHAT A THOUGHT

WHEN BARRY WAS SEVEN

BEFORE AUTUMN

THE STORY WE USED TO TELL

MY UNCLE IN THE GARDEN

PART TWO: UNCOLLECTED STORIES

ON THE HOUSE

LITTLE OLD LADY IN GREAT NEED

WHEN THINGS GET DARK

WHISTLER’S GRANDMOTHER

FAMILY MAGICIAN

THE WISHING DIME

ABOUT TWO NICE PEOPLE

MRS. MELVILLE MAKES A PURCHASE

JOURNEY WITH A LADY

THE MOST WONDERFUL THING

THE FRIENDS

ALONE IN A DEN OF CUBS

THE ORDER OF CHARLOTTE’S GOING

ONE ORDINARY DAY, WITH PEANUTS

THE MISSING GIRL

THE OMEN

THE VERY STRANGE HOUSE NEXT DOOR

A GREAT VOICE STILLED

ALL SHE SAID WAS YES

HOME

I.O.U.

THE POSSIBILITY OF EVIL

EPILOGUE: FAME

Introduction

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, A carton of cobwebbed files discovered in a Vermont barn more than a quarter century after our mother’s death arrived without notice in the mail. Within it were the original manuscript of The Haunting of Hill House, together with Shirley Jackson’s handwritten notes on character and scene development for the novel, as well as half a dozen unpublished short stories—the yellow bond carbons she kept for her files. The stories were mostly unknown to us, and we began to consider publishing a new collection of our mother’s work.

Soon we located other stories, some never published anywhere, and some published only once, decades ago, in periodicals, many long defunct. Shirley’s brother and sister-in-law, Barry and Marylou Jackson, supplied more stories in well-preserved copies of magazines; other pieces our sister, Jai Holly, and brother, Barry Hyman, had filed away over the years. Many more were found in the archives at the San Francisco Public Library. A windfall came when we learned that the Library of Congress held twenty-six cartons of our mother’s papers—journals, poetry, plays, parts of unfinished novels, and stories, lots of stories. After a week spent there photocopying, we began to feel we had the makings of a book, the first new work by Shirley Jackson since The Magic of Shirley Jackson and Come Along with Me, both published shortly after her death in 1965 at the age of forty-eight. We hoped Shirley Jackson’s work could now be discovered by a whole new generation of readers.

We uncovered a wealth of early writing from the late thirties and early forties, but very little from her precollege years. She claimed to have burned all her writings just before she left home to go to the University of Rochester, in 1934, and she may have done so, although some of her high school journals are among her preserved papers at the Library of Congress. While we could place them in a general time frame, none of the new stories we discovered had dates on them or any indication of when they were first written. Rather than be inaccurate we have left the stories in Part One undated.

Later visits to the Library of Congress enabled us to find missing parts of incomplete stories or versions that we liked better. Soon we had assembled more than 130 stories, and of these we agreed on the fifty-four presented here, those that we feel are finished and up to Shirley Jackson’s finely tuned standards. When we approached Bantam we were met with considerable enthusiasm for the project, and the book began to take shape as a significant collection of Jackson’s short fiction. Of the stories included in this collection, thirty-one have never been published before. The remaining stories had been previously published in magazines, but never before included in a collection of Jackson’s short fiction; and of these, only two or three have appeared in book form at all, mostly anthologies. One of those anthologized (and very hard to find) is “One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts.”

Many of the stories we found untitled or with working titles, since she often waited until publication to name them. In these instances we have created titles in the best muted Jackson style we could manage. In other instances we decided to change repetitive character names, often arbitrarily assigned by Jackson and intended to be changed before publication. We decided not to alter the archaic money references in these stories, however dated they may be, feeling that the integrity and understanding of the stories ought not be compromised.

We include a full range of Jackson’s many types of short fiction, from lighthearted romantic pieces to the macabre to the truly frightening. We also include a few of the humorous pieces she wrote about our family, since those, too, were what Shirley Jackson pioneered with as a writer, as well as her shocking and twisted explorations of the supernatural and the psyche. We want this collection to represent the great diversity of her work, and to show the writer’s craft evolving through a variety of forms and styles.

Our mother lived and wrote in a time—the thirties through the sixties—when smoking and drinking were both widespread and fashionable. Her characters grimly and gleefully chain-smoke and throw down drink after drink, in between boiling their coffee and spanking their children. But underneath these literary folkways of her time the universal themes glitter.

The stories we include here are not all charismatic heart-stoppers on the level of “The Lottery.” Most of her short fiction was written for publicati

on in the popular magazines of her day (Charm, Look, Harper’s, Ladies’ Home Companion, Mademoiselle, Cosmopolitan, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Reader’s Digest, The New Yorker, Playboy, Good Housekeeping, Woman’s Home Companion, etc.). She actually wrote very few horror stories, and not many stories of fantasy or the supernatural, probably preferring to develop those themes more thoroughly in her novels. She had the courage to deal with unfashionable topics and to twist popular icons. Some of the stories gathered here are so unusual in style or point of view that they resemble almost none of the rest of her work.

We discovered that some stories tried to get themselves written over and over throughout Jackson’s life. “The Honeymoon of Mrs. Smith” is shockingly different in attitude, theme, and climax from the version it precedes here, “The Mystery of the Murdered Bride.” They are the same story, told years apart and from almost opposing viewpoints. This is the only instance—but a fascinating one for students of short fiction—in which we have chosen to include two versions of the same story. We have also included a few “feel-good” stories beloved by readers of the (mostly women’s) magazines of the fifties and sixties. They are tucked between tales of murder and trickery, among ghostly rambles and poetic fables, between hugely funny family chronicles and dark tales of perfect, unexpected justice.

Our mother tried to write every day, and treated writing in every way as her professional livelihood. She would typically work all morning, after all the children went off to school, and usually again well into the evening and night. There was always the sound of typing. And our house was more often than not filled with luminaries in literature and the arts. There were legendary parties and poker games with visiting painters, sculptors, musicians, composers, poets, teachers, and writers of every leaning. But always there was the sound of her typewriter, pounding away into the night.

This collection of short fiction, taken as a whole, adds significantly to the body of Shirley Jackson’s published work. These stories range from those she wrote in college and as a budding writer living in Greenwich Village in the early forties, to those she churned out steadily during the 1950s, to those nearly perfect, terrifying pieces crafted toward the end of her life in the mid-sixties. This collection demonstrates her lifelong commitment to writing, her development as an artist, and her courage to explore universal themes of evil, madness, cruelty, and the humorous ironies of child-raising. She took the craft of writing every bit as seriously as the subject matter she chose (the Minneapolis Tribune once said: “Miss Jackson seemingly cannot write a poor sentence”) and in the work presented here the reader will find the wit and delight in storytelling that were her trademarks.

LAURENCE JACKSON HYMAN

SARAH HYMAN STEWART

San Francisco

August 1995

Preface

All I Can Remember

ALL I CAN REMEMBER clearly about being sixteen is that it was a particularly agonizing age; our family was in the process of moving East from California, and I settled down into a new high school and new manners and ways, all things that I believe produce a great uneasiness in a sixteen-year-old. I know that a chemistry class in the new high school was suspended so that I could see my first snowfall; the entire class stepped outside and amused itself watching my reactions to something I had never dreamed was real.

I also remember such a tremendous and frustrated irritation with whatever I was reading at the time—heaven knows what it could have been, considering some of the things I put away about that time—that I decided one evening that since there were no books in the world fit to read, I would write one.

After dismissing the poetic drama as outmoded and poetry as far too difficult, I finally settled on a mystery story as easiest to write and probably easiest to read. It occurred to me that if I wrote all of the story except for the end, I might put the names of all the characters into a hat and draw out one to be the murderer, thus managing to surprise even myself with the ending. I remember that I sat all day upstairs in my room, writing wildly in order to set up a situation in which one of my characters (all most unsavory, and given to adolescent wisecracks) could be chosen as the murderer. After the first two or three murders, the story got rather sketchy, because I had not enough patience to waste all that time with investigation, so I put the names of my characters together and took my manuscript downstairs to read to my family.

My mother was knitting, my father was reading a newspaper, and my brother was doing something—probably carving his initials in the coffee table—and I persuaded them all to listen to me; I read them the entire manuscript, and when I had finished, the conversation went approximately like this:

BROTHER: Whaddyou call that?

MOTHER: It’s very nice, dear.

FATHER: Very nice, very nice, (to my mother) You call the man about the furnace?

BROTHER: Only thing is, you ought to get all those people killed. (raucous laughter)

MOTHER: Shirley, in all that time upstairs I hope you remembered to make your bed.

I do not remember what character eventually came out of the hat with blood on his hands, but I do remember that I decided never to read another mystery story and never to write another mystery story; never, as a matter of fact, to write anything ever again. I had already decided finally that I was never going to be married and certainly would never have any children. It may have been about that time that I came to believe that being a private detective was the work I was meant to do.

—SHIRLEY JACKSON

PART ONE

THE SMOKING ROOM

HE WAS TALLER THAN I had imagined him. And noisier. Here I was, all by myself, downstairs in the dormitory smoking room with my typewriter, and all of a sudden there was this terrific crash and sort of sizzle, and I turned around and there he was.

“Can’t you be a little quieter?” I said. “I’m trying to work.”

He just stood there, with smoke rolling off his head. “This is as quietly as I can do it,” he said apologetically. “It takes a lot of explosive power, you know.”

“Well, explode somewhere else,” I said. “Men aren’t allowed in here.”

“I know,” he said.

I turned around to get a good look at him. He was still smoking a little, but otherwise he seemed quite a charming young man. The horns were barely noticeable, and he was wearing pointed patent leather shoes that covered his cloven hoofs. He seemed to be waiting for me to make conversation.

“You must be the devil,” I said politely, and added: “I presume.”

“Yes,” he said, pleased. “I am the devil.”

“Where’s your tail?” I demanded. He blushed and made a vague gesture with his hand.

“Circumstances…” he murmured. He came over to the table where I was working. “What’re you doing?” he asked.

“I’m writing a paper,” I said.

“Let’s see.” He reached over to the typewriter and I shoved his hand away, getting quite a nasty burn from it, too.

“Mind your own business,” I told him.

He sat down meekly. “Look,” he said, “do you have an extra cigarette?”

I threw the pack over to him and watched him light one with the tip of his finger. My hand was all inflamed where I had touched him, and it hurt.

I held out my hand to him. “You oughtn’t to treat people like that,” I said. “It makes enemies.”

He looked at my hand sympathetically, then murmured over it, and the burn vanished. “That’s better,” I said.

We sat back and smoked for a minute, looking at each other. He was a good-looking guy.

“By the way,” I said finally, “do you mind telling me what you’re here for?”

“This is a college, isn’t it?”

I looked at him for a minute, but he didn’t seem to mean anything nasty, so I said: “You are at present in the smoking room of the largest girls’ dormitory on the campus of State University, and the housemother will raise hell if she fin

ds you here.”

He began to laugh, and I realized that my choice of words had been a little silly, to say the least.

“I’d like to meet this housemother,” he said.

I tried to imagine what that would be like, and gave up. “She’s the closest thing to you you’ll find on earth,” I said earnestly.

He raised his eyebrows, and then suddenly seemed to think of something, because he reached into a pocket and pulled out a piece of paper.

“I wonder if you’d mind signing this?” he asked casually.

I picked up the paper. “May I read it first?”

He shrugged. “It isn’t important, but go ahead.”

I read: “‘This gives the devil my soul,’” and a space was left blank for my name. “This isn’t awfully legal,” I said.

He looked anxiously over my shoulder. “Isn’t it?” he said. “What’s wrong with it?”

“Well, obviously!” I threw the paper down on the table and pointed at it scornfully. “Who’s ever going to think that holds in a court of law? No witnesses, a thousand loopholes for a smart lawyer…”

He had picked up the paper and was frowning over it miserably. “It’s always been perfectly all right before,” he said.

“Well, I’m just surprised at your methods of doing business, that’s all. No court would even look at it.”

“Look,” he said. “We’ll make out another contract… one you think is all right. I don’t want to do this thing wrong, after all.”

I thought. “All right,” I said. “I’ll make one up. Mind you, I’m not awfully sure of the legal terminology, but I think I can manage.”

“Go ahead,” he said. “If it suits you, it suits me.”

I pulled the paper out of the typewriter and found a carbon and two new sheets.

He looked at the carbon suspiciously.

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

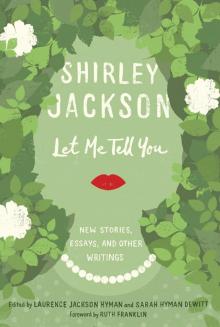

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You