- Home

Page 7

Page 7

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

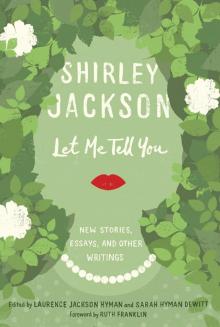

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

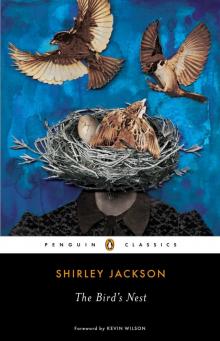

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You