- Home

- Shirley Jackson

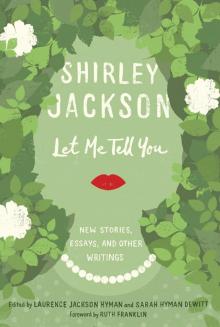

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings Page 4

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings Read online

Page 4

“With his wife,” Debbi said. “Bill Thorndyke’s wife was so jealous she couldn’t see.”

Louise ran her finger softly along the design in the couch cushion. “I don’t want to quarrel with you,” she said. “Ellen Thorndyke is worth the whole pack of you.”

“But she was jealous,” Debbi said. “Dusty told us she cried.”

I could kill them, Louise thought. “I hardly think that girl Dusty is any competent judge of emotions,” she said, hearing her voice go full of hatred.

“Well, we’ve talked about it a lot,” Debbi said seriously. “We’ve decided, among the students, that none of you could see your husbands go off to an office every day without worrying about his secretary. I mean, wives just are jealous, aren’t they?”

Come off it, come off it, Louise thought; in my own country I was accounted quite a killer. “You may be married yourself someday,” she said. “It’s just possible.”

“It’s because you don’t have anything to do,” Joan said. “Anything better, I mean.”

“What do you have to do?” Louise asked. Ellen Thorndyke was making a patchwork quilt, Jean Crown was growing orchids, Roberta Ewen had gone back to the piano. Suddenly Louise was aware that she had said all she had to say, that any more talking would destroy the handsome invulnerability she had set up for herself with such care, and she shrugged, as perfectly as Joan had shrugged a few minutes ago. “Well,” she said. “There’s no point in our arguing about it. After all, you two are leaving tomorrow.”

She gave them the correct pause of attention to indicate that they might go. They needed no prompting—not two girls who were going to spend the summer drinking scotch on yachts. They both rose, getting out of their chairs as though they were at home and the chairs were handsome antiques. They both said “Thank you so much” in the correct tones and, without looking at each other, got themselves gracefully to the door. It was clearly understood between them that before they left they were going to have to say goodbye for good; Debbi started it.

“Mrs. Harlowe,” she said, “I do want you to know that we appreciate all you’ve done.”

“You’ve been very tolerant and sympathetic,” Joan said.

“I’ve enjoyed it all so much,” Louise said. “Being here at the college has been quite an experience for both Lionel and me.” She laughed. “I think a year is enough, though.”

“Lionel says he won’t ever give up teaching,” Joan said innocently.

Louise smiled at her beautifully. “Lionel,” she said, emphasizing the word heavily, to make sure it carried to Joan, “Lionel has apparently been flattering you,” she said.

She closed the door behind them, feeling ashamed of herself and afraid of seeing Lionel. There was still time for them to get to him before he came home; there was still time for Joan to tell him sweetly, “Mrs. Harlowe asked me—”

She went out into the kitchen and made herself a drink. So I did it, she told herself defiantly. He can’t say a word without admitting everything. No more respect for his wife than that, she thought, every fat-faced little tomato who walks into his class. She took her drink back with her to the couch, and picked up the history book she was studying.

The Arabian Nights

Alice was twelve; to be precise, Alice was twelve and a day when she went to a famous nightclub with her mother and father and Mr. and Mrs. Carrington. The Carringtons were friends of her family’s, and had just arrived that day from Chicago. “So Alice was twelve years old yesterday?” Mr. Carrington had said, looking down at Alice and grinning. “Don’t you think that calls for a little celebration?” Mr. Carrington was big and cheerful and red-faced; when he said “a little celebration” it meant he wanted to spend money and show someone a good time.

Mrs. Carrington had red hair and was big and cheerful, like Mr. Carrington; Alice was very fond of both of them. “A girl’s only young once,” Mrs. Carrington had said. “This ought to be the finest celebration this old city has ever seen.”

Alice’s mother and father were cheerful people too, and they had seen to it that Alice had a very pretty twelfth birthday party; her father gave her a charm bracelet with a tiny silver cocktail shaker and glasses on it, which made her feel daring and sophisticated, and her mother gave her a manicure set with natural-color polish. Because Alice was an only child she felt very close to her mother and father, in spite of an uneasy feeling at times that they had a complete life apart from her. She knew that they were immensely popular people, that their friends were witty and charming, and that their books were good and their ideas modern; only occasionally did she wonder what they talked about all the time when they were with their friends, since they had so little to say to each other.

“Alice has never had a real grown-up celebration,” her father said. He reached for Alice, who was standing next to him, and pulled her down onto his knee. “She’s not a little girl anymore,” her father said. “She’s a young lady. What am I going to do,” he asked Mr. Carrington, “when some young man comes along and wants to take her away from me?”

“Make sure he’s rich,” Mrs. Carrington said. “If I had a daughter I’d make sure she married a man who could support Charley and me in our old age.”

“Stop mauling the child, Jamie,” Alice’s mother said. “She’s too big, and it’s undignified.”

“Two days ago I could still hold her on my lap,” Alice’s father said, “but now that she’s twelve I can’t?”

“On my fiftieth birthday,” Alice told her father, “I’ll come around and sit on your lap.”

Alice’s father began to laugh. “See, honey,” he said to his wife, “not everyone thinks it’s undignified to sit on my lap.”

Mrs. Carrington said quickly, “But what about this celebration? I propose that all of us go out somewhere to dinner, wherever Alice wants to go.”

“I want to go to the Arabian Nights,” Alice said, quickly. Everyone looked at her, and she blushed.

“What on earth?” her father said. He turned Alice’s face around. “Why do you want to go there?”

Mr. Carrington was trying very hard not to laugh. “I don’t blame her,” he said. “I’d like to go there myself. Always did want to.”

Alice held her breath. The Arabian Nights was a very big, very noisy, very famous nightclub; if she went there for dinner she could wear her new bracelet and her nail polish.

Alice’s mother was laughing too. “She must have heard Jamie talking.”

“I always wanted to go there,” Alice said to Mr. Carrington.

“If that’s where you want to have your birthday celebration,” Mr. Carrington said. “Only there must be places you’d rather go?”

“Nowhere else,” Alice said breathlessly. “I’ve been reading about it and hearing about it for a long time.”

Mr. Carrington looked at Alice’s father, and Alice’s father nodded. Then Mr. Carrington looked at Alice’s mother, and she hesitated, and then shrugged and smiled at Mrs. Carrington. Then Mr. Carrington turned to Alice. “I guess that’s it, then, Alice,” he said. “Shall I phone for a reservation?”

“Wear your blue dress,” Alice’s mother said, “and the bracelet your father gave you.”

—

Alice sat between her father and Mr. Carrington with her nails shiny and pink beyond the bracelet, in the lavishly decorated Arabian Nights, at a table that had been especially reserved. She sat with her elbow on the edge of the table, and her chin in her hand, with her shoulders pulled tight together, and she looked disdainfully at the people sitting nearby. They’re just like everyone else, she thought; I’m not afraid of any of them. When everyone had a drink—Mr. Carrington had ordered a glass of sherry for Alice—she picked it up and took a sip from it just like everyone else, and she watched how her mother toyed with the stem of her glass, and did the same thing. Seen through the glass, her fingers were long and thin.

When the floor show started, Alice had just begun her soup; her father and Mr. Carrington ate ri

ght on through in the almost-darkness and so did she. It’s canned tomato soup, like at home, she thought with surprise. They were sitting very close to the stage, and everyone had taken care that Alice should sit where she could see everything. The comedians embarrassed her because it was necessary for her to pretend not to understand them when she saw her mother glance at her and then tighten her lips to keep from smiling. Her father and Mr. Carrington were watching her too, and she was proud when she realized she was acting exactly like everyone else. The dancers delighted her; one of them came down to the edge of the stage with a bowlful of gardenias to throw to the audience, and he saw Alice and tossed her one.

“We should have thought to get her some flowers,” Mr. Carrington said as he pinned the gardenia onto Alice’s shoulder.

Intermission arrived just in time for Alice to eat her steak. The lights all went on again, and everyone turned to Alice at once and began to talk.

“Do you like the show?” her mother said.

“How are you enjoying yourself?” Mr. Carrington asked.

“Want to go home yet?” her father said.

“You look very pretty, Alice,” Mrs. Carrington said. Alice looked around at everyone and said: “I’m having a wonderful time. Everything’s wonderful.”

“Cigarette?” Mr. Carrington said to Alice very solemnly. Alice looked at her mother, and her mother shook her head. I suppose I can’t have everything, Alice thought. “No, thank you,” she said to Mr. Carrington. “I don’t smoke.” And Mr. Carrington, smiling, put the cigarette case away.

Alice’s mother was staring off at the entrance, her eyes narrow and interested, and at the same time her hand was feeling around on the table for her bag; when her hand found it, she took out her compact, still without looking, then her lipstick and comb. Finally she dropped her eyes and hurriedly opened the compact and looked at herself, touched her nose with the powder puff and her hair with the comb, turning the compact to see the sides of her hair, and then she put on a little more lipstick, and raised her eyes again to the entrance. While she looked, her hands were busy again, putting everything back into her bag and the bag back onto the table. Then suddenly she turned to Mrs. Carrington. “Look,” she said excitedly, “isn’t that Clark Gable, coming in with that party? Over there.” She gestured for Mrs. Carrington to look. “About three tables in back of Alice? I’m certain it is.” Mr. Carrington and Alice’s father were listening by this time; Mrs. Carrington gave one quick glance to the side.

“It certainly does look like him,” she said.

Alice’s father and Mr. Carrington both looked. “Sure, it’s him,” Mr. Carrington said.

“Major Gable,” Alice’s father said, “volunteered to be a top gunner during the war.”

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” whispered Mrs. Carrington to Alice’s mother.

Alice didn’t turn around, because everyone else at the table had; people all over the room were looking too, and she felt oddly conspicuous because she was so close to Mr. Gable and at a table where everyone was turning around to look.

“How soon does the floor show start again?” she asked her father.

“Pretty soon,” her father said absently. He was looking sideways at the famous man’s table.

“I’ve always thought I’d like to be an actress,” Alice’s mother said gaily. Everyone laughed.

“Look over here, Gable,” Mr. Carrington said softly, “I could use a million dollars.”

“A man like that means glamour to a lot of people,” Alice’s father said. “Made six, eight movies with Jean Harlow!”

“I remember you playing Romeo in college,” Alice’s mother said. She took her eyes off the nearby table for a minute and looked at Alice’s father. “You might be pretty,” she said, “but you sure can’t act.”

Alice’s father laughed again, unhappily. “I never had a chance to learn to be an actor anyway,” he said. “By the time I was married and had a wife and baby—”

“Shh,” Alice’s mother said, “he’s looking this way.” She looked at Mr. Carrington and smiled vivaciously. “Aren’t we silly,” she said, and threw back her head and laughed. Mrs. Carrington joined in, nudging Mr. Carrington, and Mr. Carrington sat back and guffawed. Alice’s father didn’t laugh; he sat quietly with one hand over his eyes and the other before him on the table. Alice reached out and touched his hand. When he looked up she smiled embarrassedly, and he sighed and dropped his head to his hand again. Suddenly, Alice’s mother stopped laughing and sat back in her chair. Mrs. Carrington looked around once, then picked up her glass and took a long drink from it.

Alice’s mother said across the table to Alice’s father: “You look like you just lost your last friend.”

Alice’s father dropped his hand from his eyes and sighed. “Just thinking,” he said.

“About what you might have been if you hadn’t had a wife and baby?” Alice’s mother asked. Alice looked up, surprised at her mother’s voice.

“ ‘It seems too logical…I have missed everything, even my death,’ ” Alice’s father said softly. He looked at Mrs. Carrington. “Cyrano,” he said apologetically, then laughed sadly again.

“It’s all right,” Alice’s mother said. “He isn’t looking this way anymore.”

“I’d like to meet that man,” Mrs. Carrington said. “He looks so intelligent.”

Alice’s father looked up. “Alice!” he said, and everyone listened. “Why don’t we have Alice go over and ask Gable for his autograph?” he said.

“She’s only a child, she could do it,” Alice’s mother said.

“Say, you might even ask him to join us,” Mr. Carrington said to Alice. “You know, just for a drink or something.”

“Charley,” Mrs. Carrington said reprovingly, “how could the child ask a man like that over for a drink? Anyway, he wouldn’t dream of coming.”

“He might,” Alice’s father said.

They’re all thinking he’d look over here anyway, Alice thought, and see all of them and notice them, and maybe even bow to them on his way out. “I couldn’t do that,” she said.

“Don’t be silly, darling,” her mother told her. “You’re only a child, it wouldn’t look funny.”

“She could say her mother—her mama—didn’t want her to come over,” Mrs. Carrington said, “but it’s her birthday and she wanted to meet Clark Gable.”

“I won’t do it,” Alice said.

“Alice!” her mother said.

“When I was your age,” Mrs. Carrington said heavily, “little girls minded their mothers.”

“Yes, indeed, Alice,” her mother said. “You’re not usually a disobedient child.”

“Honey,” her father said, “it’s just a joke. You only pretend, don’t you see?” He looks like the devil, she thought.

“I couldn’t pretend to want his autograph,” Alice said.

“Just tell him it’s your birthday, then,” Mr. Carrington said.

“I should think,” Mrs. Carrington whispered, “that when a little girl gets taken out to a nice party and then someone asks her to do something, she’d do it and not be so silly about it.”

“He’s leaving,” Alice’s mother said in a flat voice. Everyone turned around to look. Then they looked back at Alice.

“It’s too late now anyway,” her father said.

“Well, it doesn’t matter after all,” Mr. Carrington said finally. “It wasn’t important, Alice. Don’t worry about it.”

“I’m sorry,” Alice said to her mother.

“It doesn’t matter,” her mother said.

The lights began to dim for the second half of the floor show. Alice put her hand on Mr. Carrington’s arm. “Mr. Carrington,” she said, “I’ve got a lot of algebra to do for tomorrow, so as soon as we finish dinner could we go home?” Mr. Carrington was moving his chair to see the floor show, but he stopped for a minute and looked at her. Alice put her hands under the table and began to work the fastening of the charm b

racelet. “I’ve got all my French to do, too,” she said.

Mrs. Spencer and the Oberons

The first sign that the Oberons were coming might have been early blossoms on the peach tree, but Mrs. Spencer did not know until she got the letter. It came on Thursday, when Mrs. Spencer was already beginning to feel the first tensions of anxiety over the day, with guests invited for dinner and Donnie’s dentist appointment at three—itself requiring split-second timing at the school—and then there was the shopping to be done and the flowers to be arranged and the lemon cream to be made early this week to avoid the near catastrophe of last time, when people actually had to eat it with spoons. Now here was a strange letter in the mail.

Mrs. Spencer distrusted letters on principle, because they always seemed to want to entangle her in so many small, disagreeable obligations—visits, or news of old friends she had conveniently forgotten, or family responsibilities that always had to be met quickly and without enjoyment. If she had not persuaded herself that it was ill-bred to throw away a letter without opening it, Mrs. Spencer might very well have given up mail altogether, except for important things like Christmas cards from the right people, and announcements for the Wednesday Club, and invitations correctly engraved.

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You