- Home

- Shirley Jackson

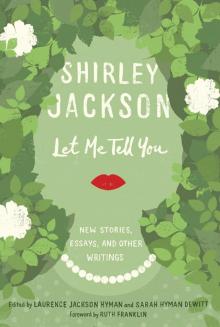

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings Page 32

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings Read online

Page 32

No cynicism can encompass, however, the infinite duplicity of children. Recently, because of dragons in the refrigerator, my husband and I found ourselves, with children, spending a totally unexpected weekend in an elaborate country inn. Because of a series of circumstances we found ourselves at table with an Anglican priest, a famous poet, and two jazz musicians, all of them absolute strangers. When we are dining with anyone outside the family, I always try to gather the children around me so that I can control them to some extent and conversation at the rest of the table can go on without too much competition. On this occasion I was not successful. Across the table, Jannie, looking incredibly small in her best yellow dress, sat between the priest and one of the jazz musicians, the trumpeter. Laurie, whose interest in jazz is absolute, had contrived to sit between the two musicians. Sally sat between the drummer and the poet. Barry sat between his father and the priest. I sat between the poet and my husband, with no child in reach, forced to rely upon an extemporaneous and elaborate system of signals and constant vigilance. A long, hard stare at each child in turn, moving meaningfully from child to napkin to child, finally got the napkins in the laps. My sign for put-that-water-glass-down-before-it-spills turned out to be a kind of flapping movement accompanied by a gasp. Eat-every-one-of-those-green-peas-with-a-fork was a baleful scowl that turned into a hasty false smile when the poet addressed me unexpectedly.

I never got much dinner, and I believe that the poet, whose good opinion I would have prized, came away with the idea that I was a kind of zany afflicted with some nervous disorder that, fortunately, had not been inherited by my children, since every child was, during the entire dinner, docile, demure, and courtly. The drummer cut Sally’s roast beef (Sally dislikes meat and does not usually touch it with even the tip of her fork), and they discussed little girls while Sally ate her roast beef. The drummer said he had a little girl just Sally’s age, and I distinctly heard Sally telling him that it was difficult for daddies to understand little girls, because they had invariably been little boys themselves. Laurie and the trumpet player dwelt lovingly upon the probable personnel of a band that seemed to be called Jelly Roll Morton and His Red Hot Peppers. Jannie, who was eating her salad as though she liked it, was conducting a spirited conversation with the priest over the sugary morality found in nineteenth-century children’s books, a subject in which I had not suspected she was so learned, although I myself had given her Elsie Dinsmore to read. Barry watched wide-eyed, answered civilly when anyone asked him how old he was, finished his milk without being told, and volunteered to the table at large a brief but enthralling account of what his nursery school teacher had said about little boys who put modeling clay into the hair of little girls. My husband and the poet talked across me about baseball. Every now and then through the general conversation I could hear one of my children saying “please” or “thank you.” When the children excused themselves and left the grown-ups to coffee, the priest remarked that they were far and away the best-behaved children he had ever seen. I thanked him and avoided looking at my husband.

—

The next night they were at home again, around their own table. Sally left her dinner in tears because she was told to eat her meat loaf or do without dessert. Jannie spilled her milk, Barry slipped all his mashed potatoes to the dog under the table, Laurie told Jannie she was a perfect absolute idiot and ought to be kept shut in her room, and Jannie said she guessed he just thought he was pretty smart but people who had such good opinions of themselves were pretty often mistaken. Barry knocked his chair over trying to get under the table to recover his napkin, Sally wailed from upstairs that she just simply hated meat loaf, and Laurie left the table abruptly, remarking with his mouth full that he was going out to play catch with Rob.

I was never so relieved in my life.

Out of the Mouths of Babes

I recently met a woman who told me, in the tone of voice these women always seem to use, that she thought of her kiddies as ambassadors of goodwill. “Goodwill,” she said clearly. “Ambassadors of goodwill. In everything they say and do, I want them to show just what kind of a little family we are,” she said.

Most of what I wanted to say I sensibly left unsaid. For one thing, it was difficult for me to control my voice. Also, it is remotely possible that her children are different from mine and all others I know, and that they really might be ambassadors of goodwill, who show in everything they say and do what kind of a little family they’re part of.

My children, of course, show in everything they say and do what kind of a little family we are. But the words that leap to mind in describing them are neither “ambassadors” nor “goodwill.” “Blabbermouths” defines more exactly the term that occurs to me. As a matter of fact, they sometimes seem to me to be a mixed bag of gossip columnists, press agents, scandalmongers, and agents provocateur. Not to put too fine a point on it, they simply cannot keep their little rosebud mouths shut.

The more personal the item, the better. And they are unerring. They know that the neighbors and the kids at school are not the least bit interested in the serious questions we all were discussing at dinner last night. What the world really wants to hear is what Daddy said when he spilled coffee on his good pants. Nor is there any way to head them off. If my husband mentions incautiously that his name was misspelled on his income tax blank and I cut in hastily to say, “Let’s not discuss this in front of the children,” the next day everyone in town knows there is something wrong with Daddy’s income tax, but it is a secret.

Some of the gabble is, of course, purely high-spirited, a genuine attempt to let the whole world in on the gay doings at our house (“You should have heard what Mommy said when the car wouldn’t start”), and some of it is purely informative (“I told the teacher Daddy said she was wrong”). Occasionally the intent of the remark—this almost always to grandparents—is clearly to make trouble (“Barry broke the airplane you gave him”). It usually succeeds.

Sometimes the honor of the family is involved. Then it is the obvious duty of the children to rally round and man the barricades (“Mrs. Brown said we were certainly getting a lot of new clothes, weren’t we, and I told her it was all right because you charged everything”). Sometimes the children—together and unafraid—feel compelled to defend their mother (“The kids in school didn’t believe what Daddy says about being able to feed an army on what you spend”).

I do not really believe that it is going to do any great harm for the neighbors to know that for Christmas, Daddy got pajamas with pictures of dancing ladies on them. As a matter of fact, if some emergency arose and he had to run into the street in the middle of the night, it would probably be just as well that the neighbors had been forewarned.

I am learning, too, to count to ten before I speak. I admit I was unwise in what I said at breakfast about Mrs. Smith and her infernal dog. But I insist that I did not say it exactly the way it was quoted to Mrs. Smith, and if she ever speaks to me again, I will tell her so.

Unraveling a knot of juvenile gossip is like getting out of an underground maze at night without a flashlight. A child comes home from school at lunchtime, quivering and furious. “I am never going to speak to my sister, Sally, ever again,” she says, “or to anyone in this whole family, because you all said Linda looked like a chorus girl.”

“Well, she does. That hair— Anyway, I never said anything of the sort.”

“You did too. And Sally told Susan and Susan told Linda and Linda told her mother and now Linda can’t invite me to her party.”

“I may have said her hair was unbecomingly arranged.”

“Linda told me her mother said I looked just as bad.”

“That’s ridiculous—although I do wish you’d comb back those bangs.”

This does not make the aggrieved one feel any better. “And now Linda is telling everyone I’m not getting a new formal for the dance just to get even,” she announces.

“And how does Linda know that?”

“Wel

l, remember when you and Daddy were talking in the study the other night? And I couldn’t sleep because you were talking so loud? And Daddy was talking about the bills?”

“And you told Linda about that, I suppose?”

“Well, she’s my best friend.”

“Susan says,” Sally observes primly, “that Linda told her that her mother thinks it’s too bad we girls dress so badly. Linda says her mother says your taste is in your feet.”

“Says that about me? When her daughter goes out dressed like something from a rummage sale?”

There is a little mollified giggle. “Wait till I tell Linda that,” Sally says.

“Now wait—wait a minute. I didn’t mean it, really.”

There is a remote possibility that someday Linda’s mother and I may find ourselves sitting together over a friendly cup of tea, sighing over the problems of teenage daughters. But somehow I am beginning to wonder. It has come to my attention that she recently remarked that our neighbors might rather have had us put the money we spent on a new car into painting that house of ours. I have since told my daughter that she may not invite Linda to her party.

Anyway, I am much more interested right now in something Barry brought home from school this morning. It seems that little Jerry Allen told him that his mommy and daddy had a terrible argument last night, and Jerry and his sister are going to stay with their grandmother for a while. I knew Mr. Allen had business troubles, because his little girl told Sally she was going to drop out of dancing school. But I can’t wait till the kids get home this afternoon to find out the rest.

The Real Me

I am tired of writing dainty little biographical things that pretend that I am a trim little housewife in a Mother Hubbard stirring up appetizing messes over a wood stove.

I live in a dank old place with a ghost that stomps around in the attic room we’ve never gone into (I think it’s walled up), and the first thing I did when we moved in was to make charms in black crayon on all the door sills and window ledges to keep out demons, and was successful in the main. There are mushrooms growing in the cellar, and a number of marble mantels that have an unexplained habit of falling down onto the heads of the neighbors’ children.

At the full of the moon I can be seen out in the backyard digging for mandrakes, of which we have a little patch, along with our rhubarb and blackberries. I do not usually care for those herbal or bat wing recipes, because you can never be sure how they will turn out. I rely almost entirely on image and number magic. My most interesting experience was with a young woman who offended me and who subsequently fell down an elevator shaft and broke all the bones in her body except one, and I didn’t know that one was there.

On Girls of Thirteen

Somewhere in our town there is a young lady I am very eager to meet. I don’t know her name or where she lives, but I know just about everything else about her. She is thirteen years old. She is allowed to cut her own hair. She is also allowed to wear lipstick all the time; she uses bright red nail polish and heavily scented bath salts, and stays up as late at night as she pleases. She wears a clean blouse to school every day and she must have a great many pairs of shoes, because she does not wear overshoes or boots in any weather. Her phone calls are not restricted, and no one ever tries to make her stop giggling. She goes to all the dances at the school and she may stay out as late as she likes afterward; she may even stop off for a banana split, although this is not surprising, since she may have all the candy and sweets and toasted cheese sandwiches she wants.

She goes to the movies on school nights. If a young man invites her to walk down to the library with him in the evening and stop off for a Coke, she doesn’t have to introduce him to her parents first. She wears quantities of cheap jewelry, her brother is never allowed to tease her, and if there is something she wants to see on television that comes on at eleven at night, or is full of shooting and screaming, she stays right up and sees it. Her mother picks up her room for her and she doesn’t have to make her bed. She has a pair of high-heeled shoes; as a matter of fact, she seems to get more new clothes every day. She goes to all the basketball games, whether she has homework or not. If a book is unsuitable for her, she has read it.

As I say, I don’t know her name or where she lives, but I’d like to get my hands on her. Just for about five minutes. She is the lowest common denominator, the altogether anonymous “everyone else” who rules the lives of thirteen-year-old girls and their miserable mothers. I hear more about her every day; if I point out that hot fudge sundaes are not the best thing for the digestion or the complexion of a young lady, or that there will be no ice skating until the top layer of junk is cleared out of that room, I hear, with a wail, that everyone else gets hot fudge sundaes, and everyone else gets to go ice skating without picking up their old rooms, and why does everyone else get all the fun instead of having cruel people around saying “work work work” all the time and she never gets a minute’s peace and it just isn’t fair. If everyone else is wearing white wool ankle socks these days, it doesn’t make any difference that white woolen ankle socks get dirty fast and are wretched to wash and dry—everyone else has handed down the word and we conform, or we are different, which is a fate roughly equivalent to being pilloried in the public square.

My older son once remarked in a fury of exasperation that if the word “he” were dropped from the English language, his sister would be speechless. This is true as far as it goes, but in order to leave her literally without a thing to say, “we” would have to be dropped, too. I heard her once trying to explain this to her younger sister, who is still in the outsider stage. “We have a crowd,” she said. “That means we all do the same things and don’t decide things by ourselves; we all do just what the others do.”

Regrettable as this sentiment may be in young people who ought by rights to be carrying around faces and minds of their own, there is no doubt about its truth. A bevy of thirteen-year-olds has only one mind, and it is the mind of everyone else. Naturally, when the mothers of thirteen-year-olds run into one another at the store, or meet at a dinner party, some of the problems can be ironed out; a simple agreement among half a dozen mothers that long black tights are not suitable for school wear can do wonders toward straightening out everyone else, and there is always the old, sometimes effective gambit “I don’t care if Carole wears red nail polish right up to her elbows, no daughter of mine…” In general, however, we mothers are trapped by the oldest con game of all—I am persuaded to give in about the movies because Linda’s mother has given in because I have given in because…

In some few areas this conformity of thought, this group identity, is valuable and fine. The group as a whole thinks college is an important objective, and so it is necessary to keep the group’s school grade average on a high level. The group has firm opinions (secondhand, of course, and not infrequently handed down by some teenage idol) on such momentous subjects as drinking and smoking (bad), learning to drive (good), showing off in public (bad, particularly if there are boys around), acting on a stage (very good indeed), and going steady (all right if everyone else is doing it and if someone asks you).

These opinions are determined by a kind of mutual idea sharing, which means everyone talking at once and telephoning people who are not around to tell them. Sometimes such a group can be moved to action far beyond the normal capacity of any individual within it, as when they go all together to clean the house for the new Girl Scout leader, or organize and run a booth at the street fair. They are tireless, except at home. There are only two ways of getting any one of them to do anything like, say, rake the leaves off the lawn. One is to nag her ceaselessly for days until she goes sullenly and gets out the rake; the other is to say, with an air of inspiration, “Why don’t we have a leaf raking party?”

Fads are not a large part of the problem. By now the teenage fad has become almost as commercial as Mother’s Day, and almost any cheap novelty comes with a label attached reading “Latest Teenage Sensation.” Od

d gadgets of dress and language and decoration are being foisted off on the kids by people who think adolescents are a ready, quick market, but in my experience no self-respecting adolescent would be caught dead with most of this junk, hula hoops and sick jokes to the contrary. Hula hoops lasted here about two days, because they were simply not as much fun as building rafts on the lake, and sick jokes have been banned by unanimous parental decree. Or at least that is what we parents believe.

No, it is the participation in group thought that is the pattern of the thirteen-year-old life, not the group thought of manufacturers of charm bracelets, or even the makers of 45-rpm records, but the group thinking of her own crew, the Lindas and the Caroles and the Cheryls and the Barbaras, who decide by a kind of spontaneous flare that one disc jockey is preferable to another, or one television program is, as of this moment, dull and another exciting. From the time my daughter gets up in the morning to brush her hair the same number of times that Carole up the street is brushing her hair to the time she turns off her radio at night after listening to the same program that Cheryl three blocks away is listening to, her life is controlled, possessed, by a shifting set of laws that make your garden-variety savage initiation rite look like milk time in the nursery school. The side of the street she walks on, the shoes she wears to walk on it, the socks, the skirt, the pocketbook (and that pocketbook is a sore point; I fought against it wildly, because it was ugly, and cheap, and impractical, but Linda had one, and Cheryl, and Patty), even the jacket and the haircut are rigidly prescribed by everyone else.

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You