- Home

- Shirley Jackson

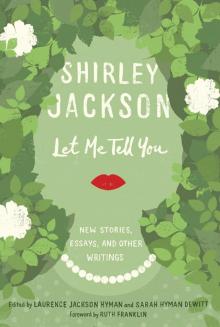

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings Page 19

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings Read online

Page 19

And then the wife has to sit across the dinner table from her husband and say: “It’s all so true, what you said in the review. I wish I had the brains to review books.”

Or consider “The Earmarked Pen.” This is something that any writer whose works appear with some regularity in any one periodical is apt to fall prey to, but I think that it is most insidious in the case of the book reviewer, who has, at best, a limited number of words at his disposal, and is prejudiced against more than half of those from the start. (Who, for instance, ever heard of someone calling a book just “good”? If a book is good, it is “eminently readable.”) Most reviewers, in fact, eventually find themselves with one or two, or at most three, personal words firmly established, like helpful relatives, in the book review as they write it; these are impossible to get rid of, and any attempt at substitution leaves the review uneasy and inclined to turn back on itself and bite.

Take, as an example, the word “heartrending.” My own reviewer is particularly attached to this word, along with “delectable” and, to a lesser extent, “invidious” (which he cannot distinguish from “insidious”) and “bailiwick.” I can recognize one of my husband’s reviews at fifty yards because somewhere in it there is going to be a paragraph beginning: “One of the most heartrending factors in this work derives from the lapse on the part of the hero, Cedric, into an invidious cad, a type of man most unsuitable for a book emphasizing the delectable character of Rosita. Removed from his own bailiwick, that of wealth and luxury, Cedric gradually deteriorates into a heartrending wreck of a man, driving Rosita into madness with his invidious insinuations….” That is “The Earmarked Pen.” I have never seen a book reviewer (or a movie reviewer or a music reviewer or an art critic) who didn’t catch it, once his first signed review brought in a check for two cents a word. There is no cure that I know of. I once gave my husband a dictionary of synonyms and a game of anagrams for his birthday, hoping they would help some. “Delectable,” he said, putting them back into the boxes, “positively heartrending.”

“The Development of the Theory of Universality in Art” comes right along with “The Development of the Theory of Style”; in other words, once he gets the idea it’s his, he’s got to pretty it up. Sooner or later your two-cents-a-word reviewer is going to turn around to his wife some evening, when she is sitting there quietly with The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club tucked inside the nine-hundred-page historical novel, and he is going to say: “Listen, I don’t see any reason why all these guys should get so much money for these books they write; it seems to me that any one-page criticism is as good as any long novel ever written, and from now on I’m an artist too, see?” I call this “The Development of the Theory of Universality in Art,” because it starts from the assumption in the reviewer’s mind that he is a writer too, only better, since reviewing can favor or condemn other artists. From that time on, the reviewer begins to think of himself as a stylist, and as a poet, too, if he can manage it.

And his reviews begin to sound like this: “When, in the course of pursuing his own heartrending and thankless brand of livelihood, the reviewer finds himself confronted with such an isolated, invidious, even incredibly desolate, comparison of his lot with that of such a delectably constructed piece of degradation as Cedric, it is not enough for one man occasionally to envy another: He must also be at some pains to suggest to himself the wicked, unhappily invidious bailiwick in which both are placed, that is to say, the sine qua non without which no book, and no reviewer, who necessarily builds from a book a new, finer, higher, and, in some cases, beautiful and lasting, form, can survive.” This is style. The poet-reviewer still gets his two cents a word, and the poet-published still gets his substantial royalties. This leads to some bitterness and eventual bad feeling, and finally review-articles beginning: “The fundamental ecological principle of art is this: No work of art, no matter how lofty, vast, or highly poetical, no matter how successful financially, can possibly expect ever to exist without the diligent application of the critic’s heartrending assistance….”

All this time I haven’t said anything about the books. That’s the reviewer’s wife’s big problem, the books. Whether she sells them or whether she sends them to the library or whether she gives them to her kid sister, they pile up in the bookcases, in packing boxes, in the corners of the living room, all incredibly pathetic in their bright shiny dust jackets, all called “The Novel of the Year” or “The New Sinclair Lewis” or “The Finest Piece of Work This Young Author Has Yet Done.” And after a certain number of books beginning:

Rosita entered the room softly and closed the door carefully behind her. Was Cedric’s presence here? Could he be? She breathed his name softly…“Cedric!”…and immediately, wonderfully, he answered! How achingly lovely, how ecstatic, it was, Rosita thought suddenly, blissfully. “Cedric,” she murmured again, “Cedric!” The heavy fragrance of roses filled the air, seeming to carry her words to him where he waited…there.

Or:

Rosie slammed the door behind her and walked over to the bed. Her high heels made a sharp clacking sound as she moved.

Ricky was asleep.

Bringing up her foot, she caught him heavily on the back of the head with her heel.

“Listen, ya punk,” she snarled, “I’ve taken enough from you, hear me? Sleep, sleep, sleep, all day long, and I’m working my fingers to the bone walking the filthy streets so you can have money to buy canned heat. Huh!”

Rosie laughed cruelly into Ricky’s wide-eyed face.

“Huh!” she said.

As I say, after so much reading starting off like this, the reviewer’s wife begins to wonder about it all. Maybe two cents a word isn’t a living wage. Maybe vacuum cleaners aren’t selling so well these days, but they’re honest. Maybe she ought to have married Cedric. Maybe she’d better call the whole heartrending thing an invidious flop.

Hex Me, Daddy, Eight to the Bar

Ever since I met one of my grandmother’s old cronies—the one with the evil eye—down on Sullivan Street the other day, I have had an uneasy feeling that I am being followed by something supernatural and malignant. Twice since then I have narrowly escaped destruction by fire, and in addition I have developed a particularly severe case of hives—out of season, I might add. In order to combat the superstitious fear that is beginning to prey on my mind, I stopped the other day in a secondhand bookstore and asked the young man on the high stool what would be good for Visitations. After some misunderstanding, the thought of which still makes me hot and cold all over, I procured a copy of a slim paperbound volume called Pow-Wows: Art and Remedies for Man and Beast.

This is by way of testimonial for John George Hohman, who compiled the book. Since I first picked up your little collection, brother, I haven’t needed another thing to keep me well and happy. From the very first remedy for mother-fits, right straight through to the punch line, the cure for wind-broken horses, it holds me. I tell you honestly that I couldn’t stir out of my chair until I had finished it. Every page is packed full of thrills. Take, for instance, page 74, with its stirring recipe for destroying spring-tails or ground-fleas. Or page 62, which explains how to “Retain the Right in Court and Council.” Let me pass that one on to all you poor devils who fear the law as I used to. It must only be employed, I might point out, when the judge is not favorably disposed toward you. You must stand in court, courageous and unabashed, and say slowly: “I appear before the house of the Judge. Three dead men look out of the window; one having no tongue, the other having no lungs, and the third being sick, blind, and dumb.” O brethren, what a cure this has worked in me! No longer do I fear the light; the haunts of the underworld see me no more, lurking in the shadows and the hidden places. No indeedy!

Sometimes Mr. Hohman is pretty short with us neophytes, all things considered. For instance, on page 30—a particular pet of mine, since it also tells me how to make cattle return home and how to cause fish to collect—we have the plaintive request: “To Prevent Cher

ries from Maturing Before Martinmas.” To which Mr. Hohman replies smartly: “Engraft the twigs on a mulberry tree, and your desire is accomplished.” That’s Hohman for you. No patience for the trivial.

Or take what we call “A Very Good Plaster,” on page 26. Mr. Hohman points out that he doubts “very much whether any physician in the United States can make a plaster equal to this.” Now it may bring the American Medical Association down on me in a fight to the finish, but I doubt also whether any physician could. You take two quarts of cider, a pound of beeswax, a pound of sheep tallow, and a pound of tobacco, and you boil it and dissolve it and strain it. The recipe doesn’t say whether you wallow in it after that, or whether you use it in your fountain pen, or whether you take one jigger of it to a glass of plain water and lots of ice please, but I tried it with a pound of oleomargarine because the grocery was fresh out of sheep tallow and it didn’t cure a thing.

Right now Hohman and I are having a lot of traffic with epileptics, always hanging around waiting for a good, quick cure. Hohman has several, provided the patient has never fallen into fire or water. Of course if the subject has ever fallen into fire or water he can take comfort from “A Safe and Approved Means to Be Applied in Cases of Fire and Pestilence” or “A Very Good Cure for Weakness of the Limbs, for the Purification of the Blood, for the Invigoration of the Head and Heart, and to Remove Giddiness, etc.” Or, as a last resort, he can desert the field completely and go in for dropsy, for which we have no fewer than eight cures. Finally, as a precaution against everything troublesome, carry the right eye of a wolf with you at all times, hidden in your right sleeve. This last charm interests me particularly, but inasmuch as I wear loose sleeves most of the time, I can’t get the right eye of anything to stay up them unless I have someone sew it in for me, and even then it would probably spoil the whole line of the shoulder.

And right near there, on page 78, there’s a system for compelling thieves to return stolen goods that doesn’t seem likely to fail: “Walk out early in the morning before sunrise to a juniper tree, and bend it with the left hand toward the rising sun, while you are saying: ‘Juniper tree, I shall bend and squeeze thee, until the thief has returned the stolen goods to the place from which he took them.’ Then you must take a stone and put it on the bush, and under the bush and the stone you must put the skull of a malefactor.” I’m going to get back all the books I ever lost, if I can find enough skulls.

Who can tell what better world lies ahead, with John George Hohman leading the way—a world free from thieves, maledictions, lawsuits, and dropsy! A world where the cherries bloom on mulberry trees, and the good old-fashioned mother-fit has stolen off into the darkness! And in this clean new world, Hohman offers me, temptingly, the power “To Dye a Madder Red.” I entertain visions of the giddier whirl, the more achingly poignant delight, the superlative, the madder red; or, possibly, the drab little madder, so quietly enduring its colorless web of days, suddenly transformed into a creature of glamour, vitality. I have dreamt of contacting herpetologist Dr. Ditmars, and bargaining with him for a few dozen (pecks? gallons? pounds?) of madders, in return for which I would dye his vampire bats or his ant colonies red, the madder red.

In the minor matters, Hohman and I can string along fine together, curing a wind-broken horse here, destroying a spring-tail there, but it all ends ultimately in disillusionment and mutual bitterness. Sand, Mr. Hohman, that’s what you’ve built on, sand. It’s page 22 that showed me—page 22, with its remedy for mortification and all. Here there is a charm to “Prevent Wicked or Malicious Persons from Doing You an Injury—Against Whom It Is of Great Power.” This remedy is simply the phrases “Dullix, ix, us; Yea, you can’t come over Pontio; Pontio is above Pilato,” to be repeated over and over until they do something. Now, I had occasion to use this charm recently, and even though it may sore disappoint John George Hohman, I feel that I ought to report my findings on it.

There is a certain Mrs. Quilter, who, besides being one of the least pleasant persons I know, has had the additional bad taste to move into a house next to mine. Not long ago she left a note in my mailbox saying that unless things got quieter fast around here she was going to complain to the police (perhaps this was due in part to a cat of mine that used to go out my back window and into hers—a long and perilous journey for a cat). Since I very rightly took no notice of her letter, a few days later I found another note from her saying that she was good and sick of the whole thing, and that it was more than human nature should be asked to stand, and that if she heard one more sound out of me (or, I suppose, my cat) she was going to Take Steps. Referring to Mr. Hohman, I wrote out the magic formula, “Dullix, ix, us; Yea, you can’t come over Pontio; Pontio is above Pilato,” and dropped it into her mailbox. I thought that would be the end of it, but she came to the door last night, in curl papers, and said, Was this infernal racket actually going to keep on? “Dullix,” I said to her quietly, “ix, us; Yea, you can’t come over Pontio; Pontio is above Pilato,” and I closed the door. This morning, the doorbell rang, and when I answered it, there was a policeman. “Well,” he remarked ominously, “what’s this I hear about you?” “Dullix—” I said. “I hear you been annoying the neighbors again,” he said. “Well, well, well.”

Frequently, however—and this is the main reason I think Hohman and I perhaps weren’t made for each other—I am made aware that maybe Hohman and his charms exist on a different level of culture from my own. And nowhere is this distressing fact borne home to me more tragically than in this recipe:

“You must go upon another person’s land and repeat the following words: ‘I go before another court—I tie up my 77-fold fits.’ Then cut three small twigs off any tree on the land; in each twig you must make a knot. This must be done on a Friday morning before sunrise, in the decrease of the moon unbeshrewedly.”

Now, leaving out the “unbeshrewedly,” which I don’t pretend to understand, I think I have a pretty good idea of what would happen if I gave this charm a good try. Suppose I were subject to fits—77-fold ones—and I wanted a good, quick cure. The only person I know with land and a tree with twigs on it is a gentleman some six houses down the block who has a good-size window box with a rosebush. Say some Friday morning I feel a fit coming on, so I take my little book under my arm and head down the street. Clambering ungracefully into the window box, I begin: “I go before another court—”

At this point the gentleman owning the window box, whose name, as I recall from the tag on the rosebush, is Pelargonium Capitatum, will open the window noisily and peer out at me nearsightedly. “What the hell do you think you are doing in that window box?” he will say. “Oh, just trying to cure a fit,” I might toss off casually. Or perhaps I might say: “Well, I have this book by this guy and it says…”

In any case, if Mr. Capitatum is an impetuous man, he will by this time have left the window to go after a phone. Or, if he has the staying power, he will be saying: “What did you just say you were trying to do?” By this time I will have reached the part in my charm where I cut three small twigs off the tree, and when he lets this go by, I have him. Then I tie a knot in each twig, and if he is the man I vaguely remember him as being, he will tell me: “Say, I used to have a sister had a little boy had fits. Tried everything, but they never cured him that way. Doctor said—”

Any long story about someone’s sister’s little boy’s fits is not best listened to in a window box; at this point I would feel constrained to slither down and say, “Well, I guess I’ll go gargle a couple of aspirin in a glass of water,” and saunter off, leaving Mr. Capitatum with his story poised in midair, his rosebush fearfully knotted, and himself with what I should diagnose, from here, as a severe—or 77-fold—convulsion.

In case anyone is interested in joining us in our work (there is still much to be done; we haven’t even touched on radioactive elements yet, or phobophobia, or the harmful substances contained in inhaled cigarette smoke), come right on over. I will be in the backyard, curing wind-broken

horses and dyeing madders a madder red. And all my old superstitious fears will have been jauntily and unbeshrewedly laid to rest.

Clowns

“What’s so special about clowns?” I’d been wondering to myself. “What makes them so funny?” (Let me say here that I intend someday to ask a clown—for instance, Emmett Kelly, that mighty creature—about people. “What’s so special about people?” I shall ask him.) Wandering around asking idiotic questions is not usually the best way to learn anything, I’d have thought, but with clowns it seems to be not how you introduce the subject but, once introduced, how you dismiss it.

“The one in the circus,” said my son with whom I began it. “The one who sweeps up the spotlight.”

“Grock,” said our friend who is a musician. “The greatest clown who ever lived, and the most unfortunate fellow.” He began to laugh reminiscently. “Let me show you,” he said; he stood up and gestured widely. “Grock used to come onto the stage, walking like this. In his bag he found first a clarinet, which he played, singing the low notes the clarinet would not sing. Then, he finds a violin, and he wishes to play that, but it is a small violin, a toy. And Grock is wearing those great gloves of the clown, so he plays the violin anyway. Like this. The small violin, and the large gloves. And he tosses the bow into the air, but cannot catch it.” The musician stopped for breath. Then, while he was tossing an imaginary violin bow into the air and pointedly not catching it, the writer interrupted.

“Remember the Marx Brothers? And the dancing scene in front of the mirror? Or Groucho’s walk? Or Harpo swinging on the opera house scenery? Or—”

“Grock, then,” the musician said, his voice rising. “He will play the piano, although it displeases him, and it plays badly, so he dismembers it. So he thinks he will play the accordion, and for a while it plays beautifully, but then he cannot make it squeeze back together again, and it grows longer and longer, until poor Grock is wound around and around. The most unfortunate fellow.”

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You