- Home

- Shirley Jackson

The Lottery and Other Stories

The Lottery and Other Stories Read online

Dedication

For my mother and father

Introduction by A. M. Homes

The world of Shirley Jackson is eerie and unforgettable. It is a place where things are not what they seem; even on a day that is sunny and clear, “with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day,” there is the threat of darkness looming, of things taking a turn for the worse. Hers is the ever-observant eye, the mind’s eye, bearing witness. Out of the stories rises a magical somnambulist’s ether—the reader is left forever changed, the mark of the stories indelible upon the imagination, the soul.

Jackson writes with a stunning simplicity; there is a graceful economy to her prose as she charts the smallest of movements, perceptual shifts—nothing pyrotechnic here. Her stories take place in small towns, in kitchens, at cocktail parties. Her characters are trapped by the petty prejudices of people who make themselves feel good by thinking they are somehow better than us all. They live in houses that need painting, in furnished rooms, inside the lives of others—as though in a psychic halfway house, having lost their footing. They are shy, unassuming folks who, for all intents and purposes, would pass through the physical world unnoticed. They care about appearances—how they are seen by others; they possess certain kinds of respectability and a healthy dose of small-town cruelty. This is about politics on the most macro of levels. There is great concern for how one is perceived, how one moves through and does—or, more likely, does not—fit into society, for everyone here is an outsider. Throughout, things are turned inside out, the private is made public, and there is the tension, the subtle electrical hum, of madness in the offing, of perpetual drama unfolding: something is going to happen, something assumedly unpleasant. Everything is thrown into relief, lit in a Hopperesque late-afternoon glow, the one-sided illumination both revealing and casting a long shadow. I can conjure the faces of each person Jackson describes, for the wear and tear over time is evident: they become bitter, pinched, they drink too much. These stories chart intention, behavior—they are an intimate exploration of the psychopathology of everyday life, the small-town sublime. When reading Jackson, I can’t help but think of the stories of Raymond Carver, who had a similar ability to create a sort of melancholy emotional mist that floats over his stories. But Jackson also had the ability to be savagely funny: at one point in her career, Desi Arnaz reportedly inquired about her interest in writing a screenplay for Lucille Ball.

The twenty-five stories in The Lottery and Other Stories—originally subtitled The Adventures of James Harris—are a generous serving of fiction. The title story, “The Lottery,” is so much an icon in the history of the American short story that one could argue it has moved from the canon of American twentieth-century fiction directly into the American psyche, our collective unconscious. And whether it is the drunken guest and the smart young girl in “The Intoxicated”—for young girls always know far more than all others, and are both understanding of and perpetually disappointed at the behavior of their elders, male elders in particular—or the well-intentioned but racist Mrs. Williams in “After You, My Dear Alphonse,” Jackson’s stories are infused with notions of morality, of children being better souls than adults, of a world where people are often persecuted for being different. What is brilliant about these stories is that Jackson presents them to us in such a way that we, the readers, can see them with great clarity and insight, yet the author is careful to allow her characters to remain in a world of their own making, to not pop the bubble.

Jackson works with precision; she sees things as if she’s zoomed in and has got life under a magnifying glass. And it’s not just any glass, but one with a curved owlish lens, so that perhaps we see and know a little more than usual. Her authorial voice is as idiosyncratic and individual as a fingerprint, and has the ring of God’s honest truth.

One of the complications of the critical response to Jackson’s work was that most critics couldn’t make sense of—or, more likely, accept—a woman writer who could produce both serious literary fiction and the far less reputable “housewife humor” that Jackson also published. Further, Jackson was not interested in being a “woman writer”; she was just a writer, neither male nor female, in a way that to this day is still not easily accommodated by the publishing industry and booksellers. And yet she managed some version of doing it all: she was a woman writer who did not compromise her vision or her talent, and she was a wife and mother of four who managed not to lose herself in some half-baked definition of what “mother” and “married” meant in a pre-feminist era. Jackson was true to her craft and her talent, and in the face of so much seeming “normality” also knew her demons, intimately, personally, but pushed on. Few women writers have been able to manage so much. Along these lines, Jackson reminds me of the late English author Angela Carter, who was also not bound by genre, who had no interest in distinguishing or separating horror, science fiction, et cetera, from “literature.” Grace Paley once described the male-female writer phenomenon to me by saying, “Women have always done men the favor of reading their work, but the men have not returned the favor.” There is a nether land, a crevasse, to be crossed by women writers who are not writing books for “women” but books for readers.

Mrs. Stanley Hyman—that was her married name; her husband was a literary critic who taught at Bennington; the town itself was the model for the town in “The Lottery.” I love thinking of Shirley Jackson as Mrs. Stanley Hyman, the writer in disguise, as the faculty wife and mother. Mrs. Stanley Hyman, just the sound of it is so of a time, the perfect cloak from which she could peer out unnoticed, observe, take notes, work otherwise unseen. Mrs. Stanley Hyman—this one’s for you.

So how does one introduce these stories—when in fact they require no introduction? They are stunning, timeless—as relevant and terrifying now as when they were first published. Her work is an absolute must for anyone aspiring to write, anyone hoping to make sense of twentieth-century American culture. Shirley Jackson is a true master.

October 2004

A. M. HOMES is the author of the novels Music for Torching, The End of Alice, In a Country of Mothers, and Jack, and the short-story collections The Safety of Objects and Things You Should Know, along with a travel memoir, Los Angeles: People, Places, and the Castle on the Hill. Her fiction and nonfiction appear frequently in many magazines, including The New Yorker, Granta, McSweeney’s, Harper’s, Zoetrope, The New York Times, and Vanity Fair, for which she is a contributing editor.

I

The Intoxicated

HE WAS JUST TIGHT ENOUGH and just familiar enough with the house to be able to go out into the kitchen alone, apparently to get ice, but actually to sober up a little; he was not quite enough a friend of the family to pass out on the living-room couch. He left the party behind without reluctance, the group by the piano singing “Stardust,” his hostess talking earnestly to a young man with thin clean glasses and a sullen mouth; he walked guardedly through the dining-room where a little group of four or five people sat on the stiff chairs reasoning something out carefully among themselves; the kitchen doors swung abruptly to his touch, and he sat down beside a white enamel table, clean and cold under his hand. He put his glass on a good spot in the green pattern and looked up to find that a young girl was regarding him speculatively from across the table.

“Hello,” he said. “You the daughter?”

“I’m Eileen,” she said. “Yes.”

She seemed to him baggy and ill-formed; it’s the clothes they wear now, young girls, he thought foggily; her hair was braided down either side of her face, and she looked young and fresh and not dressed-up; her sweater was purplish and her hair was dark. “You sound nice and sober,” he said, realizing that it was the wrong t

hing to say to young girls.

“I was just having a cup of coffee,” she said. “May I get you one?”

He almost laughed, thinking that she expected she was dealing knowingly and competently with a rude drunk. “Thank you,” he said, “I believe I will.” He made an effort to focus his eyes; the coffee was hot, and when she put a cup in front of him, saying, “I suppose you’d like it black,” he put his face into the steam and let it go into his eyes, hoping to clear his head.

“It sounds like a lovely party,” she said without longing, “everyone must be having a fine time.”

“It is a lovely party.” He began to drink the coffee, scalding hot, wanting her to know she had helped him. His head steadied, and he smiled at her. “I feel better,” he said, “thanks to you.”

“It must be very warm in the other room,” she said soothingly.

Then he did laugh out loud and she frowned, but he could see her excusing him as she went on, “It was so hot upstairs I thought I’d like to come down for a while and sit out here.”

“Were you asleep?” he asked. “Did we wake you?”

“I was doing my homework,” she said.

He looked at her again, seeing her against a background of careful penmanship and themes, worn textbooks and laughter between desks. “You’re in high school?”

“I’m a Senior.” She seemed to wait for him to say something, and then she said, “I was out a year when I had pneumonia.”

He found it difficult to think of something to say (ask her about boys? basketball?), and so he pretended he was listening to the distant noises from the front of the house. “It’s a fine party,” he said again, vaguely.

“I suppose you like parties,” she said.

Dumbfounded, he sat staring into his empty coffee cup. He supposed he did like parties; her tone had been faintly surprised, as though next he were to declare for an arena with gladiators fighting wild beasts, or the solitary circular waltzing of a madman in a garden. I’m almost twice your age, my girl, he thought, but it’s not so long since I did homework too. “Play basketball?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

He felt with irritation that she had been in the kitchen first, that she lived in the house, that he must keep on talking to her. “What’s your homework about?” he asked.

“I’m writing a paper on the future of the world,” she said, and smiled. “It sounds silly, doesn’t it? I think it’s silly.”

“Your party out front is talking about it. That’s one reason I came out here.” He could see her thinking that that was not at all the reason he came out here, and he said quickly, “What are you saying about the future of the world?”

“I don’t really think it’s got much future,” she said, “at least the way we’ve got it now.”

“It’s an interesting time to be alive,” he said, as though he were still at the party.

“Well, after all,” she said, “it isn’t as though we didn’t know about it in advance.”

He looked at her for a minute; she was staring absently at the toe of her saddle shoe, moving her foot softly back and forth, following it with her eyes. “It’s really a frightening time when a girl sixteen has to think of things like that.” In my day, he thought of saying mockingly, girls thought of nothing but cocktails and necking.

“I’m seventeen.” She looked up and smiled at him again. “There’s a terrible difference,” she said.

“In my day,” he said, overemphasizing, “girls thought of nothing but cocktails and necking.”

“That’s partly the trouble,” she answered him seriously. “If people had been really, honestly scared when you were young we wouldn’t be so badly off today.”

His voice had more of an edge than he intended (“When I was young!”), and he turned partly away from her as though to indicate the half-interest of an older person being gracious to a child: “I imagine we thought we were scared. I imagine all kids sixteen—seventeen—think they’re scared. It’s part of a stage you go through, like being boy-crazy.”

“I keep figuring how it will be.” She spoke very softly, very clearly, to a point just past him on the wall. “Somehow I think of the churches as going first, before even the Empire State building. And then all the big apartment houses by the river, slipping down slowly into the water with the people inside. And the schools, in the middle of Latin class maybe, while we’re reading Cæsar.” She brought her eyes to his face, looking at him in numb excitement. “Each time we begin a chapter in Cæsar, I wonder if this won’t be the one we never finish. Maybe we in our Latin class will be the last people who ever read Cæsar.”

“That would be good news,” he said lightly. “I used to hate Cæsar.”

“I suppose when you were young everyone hated Cæsar,” she said coolly.

He waited for a minute before he said, “I think it’s a little silly for you to fill your mind with all this morbid trash. Buy yourself a movie magazine and settle down.”

“I’ll be able to get all the movie magazines I want,” she said insistently. “The subways will crash through, you know, and the little magazine stands will all be squashed. You’ll be able to pick up all the candy bars you want, and magazines, and lipsticks and artificial flowers from the five-and-ten, and dresses lying in the street from all the big stores. And fur coats.”

“I hope the liquor stores will break wide open,” he said, beginning to feel impatient with her, “I’d walk in and help myself to a case of brandy and never worry about anything again.”

“The office buildings will be just piles of broken stones,” she said, her wide emphatic eyes still looking at him. “If only you could know exactly what minute it will come.”

“I see,” he said. “I go with the rest. I see.”

“Things will be different afterward,” she said. “Everything that makes the world like it is now will be gone. We’ll have new rules and new ways of living. Maybe there’ll be a law not to live in houses, so then no one can hide from anyone else, you see.”

“Maybe there’ll be a law to keep all seventeen-year-old girls in school learning sense,” he said, standing up.

“There won’t be any schools,” she said flatly. “No one will learn anything. To keep from getting back where we are now.”

“Well,” he said, with a little laugh. “You make it sound very interesting. Sorry I won’t be there to see it.” He stopped, his shoulder against the swinging door into the dining-room. He wanted badly to say something adult and scathing, and yet he was afraid of showing her that he had listened to her, that when he was young people had not talked like that. “If you have any trouble with your Latin,” he said finally, “I’ll be glad to give you a hand.”

She giggled, shocking him. “I still do my homework every night,” she said.

Back in the living-room, with people moving cheerfully around him, the group by the piano now singing “Home on the Range,” his hostess deep in earnest conversation with a tall, graceful man in a blue suit, he found the girl’s father and said, “I’ve just been having a very interesting conversation with your daughter.”

His host’s eye moved quickly around the room. “Eileen? Where is she?”

“In the kitchen. She’s doing her Latin.”

“‘Gallia est omnia divisa in partes tres,’” his host said without expression. “I know.”

“A really extraordinary girl.”

His host shook his head ruefully. “Kids nowadays,” he said.

The Daemon Lover

SHE HAD NOT SLEPT WELL; from one-thirty, when Jamie left and she went lingeringly to bed, until seven, when she at last allowed herself to get up and make coffee, she had slept fitfully, stirring awake to open her eyes and look into the half-darkness, remembering over and over, slipping again into a feverish dream. She spent almost an hour over her coffee—they were to have a real breakfast on the way—and then, unless she wanted to dress early, had nothing to do. She washed her coffee cup and made the bed, looking

carefully over the clothes she planned to wear, worried unnecessarily, at the window, over whether it would be a fine day. She sat down to read, thought that she might write a letter to her sister instead, and began, in her finest handwriting, “Dearest Anne, by the time you get this I will be married. Doesn’t it sound funny? I can hardly believe it myself, but when I tell you how it happened, you’ll see it’s even stranger than that….”

Sitting, pen in hand, she hesitated over what to say next, read the lines already written, and tore up the letter. She went to the window and saw that it was undeniably a fine day. It occurred to her that perhaps she ought not to wear the blue silk dress; it was too plain, almost severe, and she wanted to be soft, feminine. Anxiously she pulled through the dresses in the closet, and hesitated over a print she had worn the summer before; it was too young for her, and it had a ruffled neck, and it was very early in the year for a print dress, but still….

She hung the two dresses side by side on the outside of the closet door and opened the glass doors carefully closed upon the small closet that was her kitchenette. She turned on the burner under the coffeepot, and went to the window; it was sunny. When the coffeepot began to crackle she came back and poured herself coffee, into a clean cup. I’ll have a headache if I don’t get some solid food soon, she thought, all this coffee, smoking too much, no real breakfast. A headache on her wedding day; she went and got the tin box of aspirin from the bathroom closet and slipped it into her blue pocketbook. She’d have to change to a brown pocketbook if she wore the print dress, and the only brown pocketbook she had was shabby. Helplessly, she stood looking from the blue pocketbook to the print dress, and then put the pocketbook down and went and got her coffee and sat down near the window, drinking her coffee, and looking carefully around the one-room apartment. They planned to come back here tonight and everything must be correct. With sudden horror she realized that she had forgotten to put clean sheets on the bed; the laundry was freshly back and she took clean sheets and pillow cases from the top shelf of the closet and stripped the bed, working quickly to avoid thinking consciously of why she was changing the sheets. The bed was a studio bed, with a cover to make it look like a couch, and when it was finished no one would have known she had just put clean sheets on it. She took the old sheets and pillow cases into the bathroom and stuffed them down into the hamper, and put the bathroom towels in the hamper too, and clean towels on the bathroom racks. Her coffee was cold when she came back to it, but she drank it anyway.

The Road Through the Wall

The Road Through the Wall Hangsaman

Hangsaman Come Along With Me

Come Along With Me The Lottery

The Lottery Just an Ordinary Day: Stories

Just an Ordinary Day: Stories The Sundial

The Sundial Dark Tales

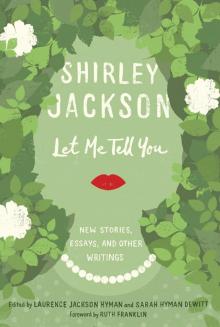

Dark Tales Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings

Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings The Haunting of Hill House

The Haunting of Hill House The Bird's Nest

The Bird's Nest Raising Demons

Raising Demons We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle The Letters of Shirley Jackson

The Letters of Shirley Jackson The Missing Girl

The Missing Girl Let Me Tell You

Let Me Tell You